Error message

INTRODUCTION | After more than 40 years of very low birth rates, Japan now has one of the oldest populations in the world. Sustained low birth rates mean that there are few children in the population and eventually few working-age adults to drive economic growth and support the relatively large proportion of elderly, who were born in a previous era when fertility was higher. But why are young Japanese having so few children? One reason appears to be the uncertain employment prospects for young men, which make them poor candidates for marriage. The persistence of strong gender differences in housework and childcare also make the "marriage package" unattractive for Japanese women. Over the years, the Japanese government has introduced and expanded several programs to encourage young Japanese to marry and have children, including parental leave, monetary assistance to parents, and highly subsidized childcare. So far, however, these programs appear to have had very little impact.

A Long History of Fertility Decline

From shortly after World War II to the late 1950s, Japan experienced a steep drop in fertility. In a little more than one decade, the birth rate went down by more than one-half, from a total fertility rate (TFR) of 4.5 children per woman in 1947 to 2.0 in 1957. Fertility at this "replacement" level leads to a stable population age structure and size. But then in the mid-1970s, childbearing in Japan started dropping further. Since 2000, Japan’s TFR has fluctuated between 1.3 and 1.4 children per woman.

Birthrates this low have led to extreme population aging and even population decline. As of 2015, 27 percent of Japan's population was age 65 and above, and projections indicate that by 2060 roughly 40 percent of Japan's population will be elderly. Japan is also the first large country in the world whose overall population is becoming smaller in prosperous and peaceful times. And projections suggest that the Japanese population will decline steadily over the next several decades—from 128 million in 2010 to around 87 million by 2060. Population aging and population decline on this scale pose serious challenges for Japan's economy and the wellbeing of the Japanese people.

During Japan's first period of fertility decline, most young men and women still married, but they had fewer children within marriage. By contrast, the fertility decline that began in the 1970s has been accompanied by sharply decreasing rates of marriage. As of 2010, 11 percent of women and 20 percent of men at age 50 had never been married, and the trend shows no sign of reversing. Because childbearing outside of marriage is rare, this low marriage rate means that many Japanese men and women will never have children.

Yet Japanese support systems are designed with family as the primary safety net, particularly for care and support of the elderly. Given this framework, the rapid expansion of the number of single men and women—who will grow old without children or grandchildren—has profound implications for the economic status and wellbeing of Japan's population in years to come.

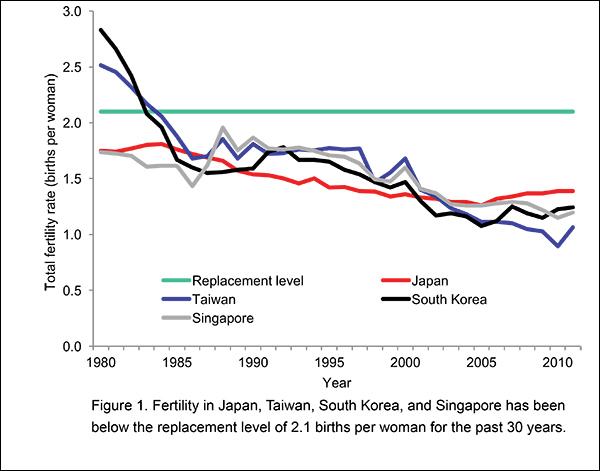

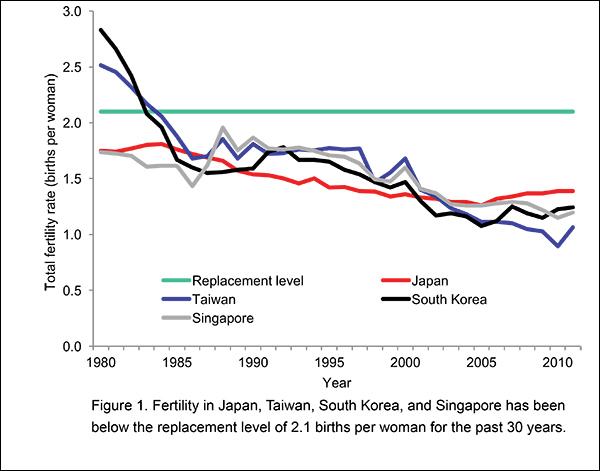

And this problem is not confined to Japan. Although Japan was the first country in Asia that experienced such a steep and prolonged fertility decline, by now fertility has dropped to similar levels—or even slightly lower—in other advanced economies of the region (Figure 1).

Why Are Birth Rates So Low?

In Japan, the reluctance to marry or have children has most likely arisen, at least in part, from shrinking employment opportunities for young men. In 1960, 97 percent of men age 25-29 were employed, but by 2010 this number had dropped to 86 percent. Over the same period, young women's employment rates increased dramatically—from 50 percent in 1960 to 72 percent in 2010.

Even more important than overall employment rates, a large proportion of the young men who are employed today are in temporary jobs, very likely affecting their marriage prospects. And if men's limited and precarious employment opportunities make them poor candidates for marriage, then Japan's fertility is likely to remain very low for some time to come.

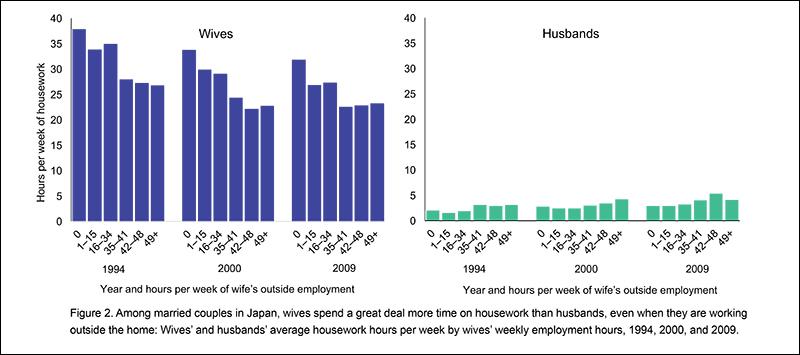

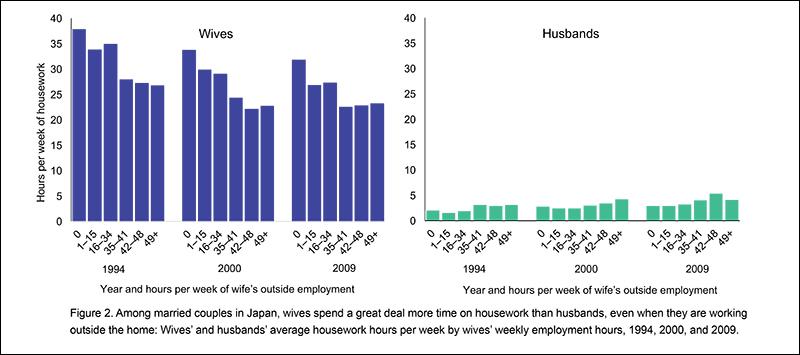

Another factor that may be affecting marriage rates is the persistence of a traditional gender division of labor that places heavy obligations on women for household maintenance and childcare. In 2009, Japanese wives at reproductive ages spent an average of 27 hours per week on household tasks (not including childcare), while husbands spent an average of 3 hours per week (Figure 2). Even women who were employed fulltime spent more than 20 hours per week on housework. And women's employment obligations appeared to have very little effect on men's contribution to household tasks, which never exceeded 5.3 hours per week on average.

Apart from household tasks, parenting in Japan tends to be particularly intensive, and it is overwhelmingly the mother who is responsible for looking after children's daily needs and making sure they succeed in a highly competitive education system. Women all over the world spend more time on housework and childcare than men, but the differences in Japan are extreme.

An Insufficient Government Response

Apart from improving gender relations in the home, the most promising option for reversing the downward trend in marriage and childbearing seems to be through government programs that make marriage and parenthood more attractive by helping couples balance their work and domestic obligations. And in Japan, public pressure to initiate and expand such programs has been strong.

In 1989, the total fertility rate in Japan dropped to a new low of 1.57 births per woman, and in 1990, when the drop in fertility was recognized, the "1.57 Shock" made media headlines throughout the country. Since then, the Japanese government has initiated and expanded family policies and programs over and over again. Support for young families is offered primarily in three areas: (1) monetary assistance in the form of child allowances paid directly to parents; (2) steadily expanding provisions for parental leave; and (3) subsidized childcare services.

Launched in 1972, a child-allowance scheme initially covered third and higher-order children in households with incomes below a certain threshold. The duration of payment was from a child's birth to graduation from junior high school. Today the scheme is still income tested, but it has expanded to include first and second children. The amount of the allowance has also increased, although it is still modest. As of 2012, the government pays low-income parents an allowance for each child ranging from US$100 to US$150 per month.

Beginning in 1992, the government has offered 12 months of parental leave for parents who meet minimum work requirements. Income compensation was added in 1995 and is now paid at 50 percent of the monthly salary prior to the beginning of leave. Japan’s parental-leave scheme has major shortcomings, however, including rather stringent limitations on coverage, a low level of income compensation, and, most importantly, lack of legally binding authority. As of 2010, parental leave was available in most large and medium-size organizations but in only 40 percent of companies with fewer than 30 employees. And about one-third of women employees work in such small organizations.

In 1994, the government launched a succession of programs designed to expand childcare services and encourage the workplace to become more family friendly. The number of children enrolled in daycare has increased since 2000, but the number on waiting lists has also gone up, indicating that the demand for childcare is growing faster than the supply. In particular, there is an acute shortage of childcare services in Japan's large cities.

Families Still Strained and Fertility Remains Low

Despite these government programs, Japan's family policy appears to have been largely ineffective. Strains on parents, especially working mothers, have not been significantly alleviated, and fertility has increased very slightly—from 1.26 children per woman (the lowest recorded) in 2005 to 1.45 in 2015.

Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan have had similar experiences. All three countries offer paid parental leave and subsidized childcare, and Singapore—like Japan—offers cash payments to families with children. Yet fertility remains stubbornly low.

Japan's sluggish economic growth makes it difficult to expand family support programs, but still, the government could probably do better. Comparing 18 member countries, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) ranked Japan second from the bottom in policies for work-family reconciliation and family-friendly work arrangements. The OECD pointed out that Japan's childcare services and the parental leave offered by employers are particularly weak.

This suggests that it is critically important for the Japanese government to strengthen efforts to help working parents of small children by expanding affordable childcare services. It is also important to make the workplace more flexible and family friendly, including expanding the coverage of parental leave and changing Japan's corporate culture that places emphasis on long work hours, frequent overtime work, and mandatory after-hours socializing with colleagues. Given the serious, long-term economic and social consequences of very low fertility, Japan has no choice but to strengthen policies and society-wide efforts to help couples make work and family life more compatible.

Notes

This AsiaPacific Issues paper is based on Noriko O. Tsuya (2015), Below-replacement fertility in Japan: Patterns, factors, and policy implications. In Ronald R. Rindfuss and Minja Kim Choe (eds.), Low and lower fertility: Variations across developed countries. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. Comparative information comes from Gavin W. Jones and Wajihah Hamid (2015), Singapore’s pro-natalist policies: To what extent have they worked? in the same volume.

About the Author

Noriko O. Tsuya is professor, Faculty of Economics, Keio University in Tokyo. Her research focuses on fertility and family change in Japan and developed countries.

She can be reached at: [email protected]

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Center.

Photo: Richard Bailey/Getty Images

INTRODUCTION | After more than 40 years of very low birth rates, Japan now has one of the oldest populations in the world. Sustained low birth rates mean that there are few children in the population and eventually few working-age adults to drive economic growth and support the relatively large proportion of elderly, who were born in a previous era when fertility was higher. But why are young Japanese having so few children? One reason appears to be the uncertain employment prospects for young men, which make them poor candidates for marriage. The persistence of strong gender differences in housework and childcare also make the "marriage package" unattractive for Japanese women. Over the years, the Japanese government has introduced and expanded several programs to encourage young Japanese to marry and have children, including parental leave, monetary assistance to parents, and highly subsidized childcare. So far, however, these programs appear to have had very little impact.

A Long History of Fertility Decline

From shortly after World War II to the late 1950s, Japan experienced a steep drop in fertility. In a little more than one decade, the birth rate went down by more than one-half, from a total fertility rate (TFR) of 4.5 children per woman in 1947 to 2.0 in 1957. Fertility at this "replacement" level leads to a stable population age structure and size. But then in the mid-1970s, childbearing in Japan started dropping further. Since 2000, Japan’s TFR has fluctuated between 1.3 and 1.4 children per woman.

Birthrates this low have led to extreme population aging and even population decline. As of 2015, 27 percent of Japan's population was age 65 and above, and projections indicate that by 2060 roughly 40 percent of Japan's population will be elderly. Japan is also the first large country in the world whose overall population is becoming smaller in prosperous and peaceful times. And projections suggest that the Japanese population will decline steadily over the next several decades—from 128 million in 2010 to around 87 million by 2060. Population aging and population decline on this scale pose serious challenges for Japan's economy and the wellbeing of the Japanese people.

During Japan's first period of fertility decline, most young men and women still married, but they had fewer children within marriage. By contrast, the fertility decline that began in the 1970s has been accompanied by sharply decreasing rates of marriage. As of 2010, 11 percent of women and 20 percent of men at age 50 had never been married, and the trend shows no sign of reversing. Because childbearing outside of marriage is rare, this low marriage rate means that many Japanese men and women will never have children.

Yet Japanese support systems are designed with family as the primary safety net, particularly for care and support of the elderly. Given this framework, the rapid expansion of the number of single men and women—who will grow old without children or grandchildren—has profound implications for the economic status and wellbeing of Japan's population in years to come.

And this problem is not confined to Japan. Although Japan was the first country in Asia that experienced such a steep and prolonged fertility decline, by now fertility has dropped to similar levels—or even slightly lower—in other advanced economies of the region (Figure 1).

Why Are Birth Rates So Low?

In Japan, the reluctance to marry or have children has most likely arisen, at least in part, from shrinking employment opportunities for young men. In 1960, 97 percent of men age 25-29 were employed, but by 2010 this number had dropped to 86 percent. Over the same period, young women's employment rates increased dramatically—from 50 percent in 1960 to 72 percent in 2010.

Even more important than overall employment rates, a large proportion of the young men who are employed today are in temporary jobs, very likely affecting their marriage prospects. And if men's limited and precarious employment opportunities make them poor candidates for marriage, then Japan's fertility is likely to remain very low for some time to come.

Another factor that may be affecting marriage rates is the persistence of a traditional gender division of labor that places heavy obligations on women for household maintenance and childcare. In 2009, Japanese wives at reproductive ages spent an average of 27 hours per week on household tasks (not including childcare), while husbands spent an average of 3 hours per week (Figure 2). Even women who were employed fulltime spent more than 20 hours per week on housework. And women's employment obligations appeared to have very little effect on men's contribution to household tasks, which never exceeded 5.3 hours per week on average.

Apart from household tasks, parenting in Japan tends to be particularly intensive, and it is overwhelmingly the mother who is responsible for looking after children's daily needs and making sure they succeed in a highly competitive education system. Women all over the world spend more time on housework and childcare than men, but the differences in Japan are extreme.

An Insufficient Government Response

Apart from improving gender relations in the home, the most promising option for reversing the downward trend in marriage and childbearing seems to be through government programs that make marriage and parenthood more attractive by helping couples balance their work and domestic obligations. And in Japan, public pressure to initiate and expand such programs has been strong.

In 1989, the total fertility rate in Japan dropped to a new low of 1.57 births per woman, and in 1990, when the drop in fertility was recognized, the "1.57 Shock" made media headlines throughout the country. Since then, the Japanese government has initiated and expanded family policies and programs over and over again. Support for young families is offered primarily in three areas: (1) monetary assistance in the form of child allowances paid directly to parents; (2) steadily expanding provisions for parental leave; and (3) subsidized childcare services.

Launched in 1972, a child-allowance scheme initially covered third and higher-order children in households with incomes below a certain threshold. The duration of payment was from a child's birth to graduation from junior high school. Today the scheme is still income tested, but it has expanded to include first and second children. The amount of the allowance has also increased, although it is still modest. As of 2012, the government pays low-income parents an allowance for each child ranging from US$100 to US$150 per month.

Beginning in 1992, the government has offered 12 months of parental leave for parents who meet minimum work requirements. Income compensation was added in 1995 and is now paid at 50 percent of the monthly salary prior to the beginning of leave. Japan’s parental-leave scheme has major shortcomings, however, including rather stringent limitations on coverage, a low level of income compensation, and, most importantly, lack of legally binding authority. As of 2010, parental leave was available in most large and medium-size organizations but in only 40 percent of companies with fewer than 30 employees. And about one-third of women employees work in such small organizations.

In 1994, the government launched a succession of programs designed to expand childcare services and encourage the workplace to become more family friendly. The number of children enrolled in daycare has increased since 2000, but the number on waiting lists has also gone up, indicating that the demand for childcare is growing faster than the supply. In particular, there is an acute shortage of childcare services in Japan's large cities.

Families Still Strained and Fertility Remains Low

Despite these government programs, Japan's family policy appears to have been largely ineffective. Strains on parents, especially working mothers, have not been significantly alleviated, and fertility has increased very slightly—from 1.26 children per woman (the lowest recorded) in 2005 to 1.45 in 2015.

Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan have had similar experiences. All three countries offer paid parental leave and subsidized childcare, and Singapore—like Japan—offers cash payments to families with children. Yet fertility remains stubbornly low.

Japan's sluggish economic growth makes it difficult to expand family support programs, but still, the government could probably do better. Comparing 18 member countries, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) ranked Japan second from the bottom in policies for work-family reconciliation and family-friendly work arrangements. The OECD pointed out that Japan's childcare services and the parental leave offered by employers are particularly weak.

This suggests that it is critically important for the Japanese government to strengthen efforts to help working parents of small children by expanding affordable childcare services. It is also important to make the workplace more flexible and family friendly, including expanding the coverage of parental leave and changing Japan's corporate culture that places emphasis on long work hours, frequent overtime work, and mandatory after-hours socializing with colleagues. Given the serious, long-term economic and social consequences of very low fertility, Japan has no choice but to strengthen policies and society-wide efforts to help couples make work and family life more compatible.

Notes

This AsiaPacific Issues paper is based on Noriko O. Tsuya (2015), Below-replacement fertility in Japan: Patterns, factors, and policy implications. In Ronald R. Rindfuss and Minja Kim Choe (eds.), Low and lower fertility: Variations across developed countries. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. Comparative information comes from Gavin W. Jones and Wajihah Hamid (2015), Singapore’s pro-natalist policies: To what extent have they worked? in the same volume.

About the Author

Noriko O. Tsuya is professor, Faculty of Economics, Keio University in Tokyo. Her research focuses on fertility and family change in Japan and developed countries.

She can be reached at: [email protected]

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Center.

Photo: Richard Bailey/Getty Images