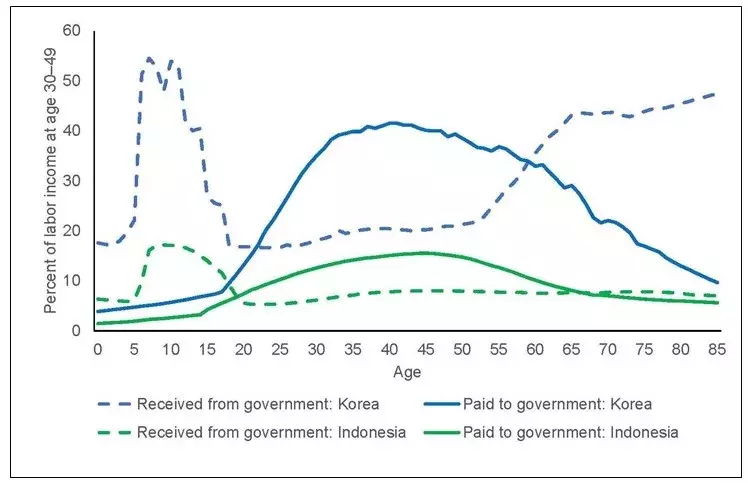

Taxes paid and benefits received from the government are much higher in South Korea than in Indonesia, reflecting higher expenditures on public education for the young and pension and healthcare programs for the elderly.

By Andrew Mason, Sang-Hyop Lee, and Donghyun Park

HONOLULU (8 May 2020)—Elderly populations in Asia are expanding more quickly than other age groups. Low fertility rates result in fewer children and eventually fewer working-age adults, while elderly populations are living longer.

This trend began at different times in different countries and is occurring at different rates, but it is common everywhere. It has two major impacts: demand for income support for the elderly will rise because their labor income tends to be extremely low; and gross domestic product (GDP) and other aggregate economic indicators will grow more slowly as growth in the effective labor force declines and in some instances even shrinks. Policymakers across the continent face the same challenge—how to maintain economic dynamism while at the same time creating transparent and equitable mechanisms to assure some level of economic security for the elderly.

The demands for income support will be substantial. In East Asia, by 2060, more than 40 percent of the total labor income of the entire population will be needed just to fund elderly consumption beyond their own labor income. The outsized requirement for resources in East Asia stems from large elderly populations with low levels of per capita labor income and high levels of per capita consumption. In other parts of Asia, where populations are younger, elderly needs will require closer to 20 percent of total labor income.

Two sources of income for the elderly

In addition to modest labor income, resources for the elderly come from assets accumulated earlier in life and transfers from younger generations. Transfers between generations may occur within families or, increasingly, through government pensions and healthcare programs funded by tax payers. A critical challenge for policymakers is to find the right balance for old-age support by encouraging saving, supporting families, and providing a safety net of public support. Relying exclusively on just one of these options spells trouble.

Assets. Many working-age adults accumulate assets in anticipation of their retirement. They may participate in funded pension programs, buy a home, or accumulate assets in many other ways. In some countries—for example, Singapore—the accumulation of retirement assets is mandated by law.

However, to fully meet retirement needs would require massive increases in assets. In Japan by 2060, the assets required to fully fund retirement would be about eight times GDP. In China, the assets required would be less than twice GDP. Although China’s challenge would be much more modest that Japan’s, relying exclusively on assets to fund old-age needs would not be realistic in any country.

Transfers from the younger generation. Overall, family support for the elderly is increasingly giving way to the public sector. Unfortunately, just as these demands are rising, the taxes that fund government pensions and healthcare programs will have to be drawn from a declining working-age population. As labor income declines relative to needs, governments with particularly large public programs for the elderly are at greatest risk of financial stress.

Among Asian countries, the importance of public programs varies widely. In general, lower-income countries have much more modest public sectors than higher-income countries. This is illustrated by the chart comparing funds paid into the public sector (primarily taxes) and funds paid out from the public sector (including education, pensions, and healthcare, among other programs) in Indonesia and South Korea.

Although Korea’s public sector is smaller than that of many rich countries, it is much larger than Indonesia’s. As shown in the figure, at peak ages (early 40s), Koreans pay about 40 percent of their average labor income to the government, compared with about 15 percent in Indonesia.

The magnitude of government benefits also differs markedly. Public resources flowing to children are particularly high in Korea, reflecting large public investment in education. Resources flowing to the elderly are also much higher in Korea.

What are the options?

In the absence of reforms to boost economic growth or curtail the growth of retirement needs, tax revenues will rise more slowly than pension and healthcare benefits as populations age. In countries where government programs play an important role in old-age support, tax rates will have to rise more quickly or benefits will have to be curtailed or both—all options with significant political costs.

As a practical matter, the elderly rely on a combination of public transfers and saving to fund old-age needs. But which mix is best? High rates of saving, when invested productively, lead to capital accumulation and a rise in labor income. By contrast, transfers only move resources from one age group to another—there is no increase in capital or productivity.

In this respect, Asia has an advantage compared to many aging countries in Europe and Latin America. Many Asian countries rely heavily on assets rather than transfers to meet retirement consumption needs. In Japan, for example, about one-half of old-age needs are funded by assets and about one-half by transfers.Policies that promote economic growth can help ease the pressure on government budgets because people who earn more generally save more and they also pay more taxes. Investment in education and technology tends to raise worker productivity, resulting in higher earnings. Lifetime earnings are also higher in countries where young people find good-paying jobs soon after they finish school and where workers retire relatively late in life. In addition, overall labor income is higher in societies where women and older men earn salaries close to those of middle-aged men. Finally, governments need to ensure sound and transparent financial institutions that will encourage people to save for retirement. Policies such as these will contribute to both old-age economic security and economic growth.

###

Download a pdf version of this Wire article.

This East-West Wire is based on Demographic change, economic growth, and old-age economic security: Asia and the world, by Andrew Mason, Sang-Hyop Lee, and Donghyun Park. Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2020.

Andrew Mason is a Senior Fellow at the East-West Center. He can be reached at [email protected]. Sang-Hyop Lee is a Senior Fellow at the East-West Center and Professor of Economics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He can be reached at [email protected]. Donghyun Park is Principal Economist at the Asian Development Bank. He can be reached at [email protected].

The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the East-West Center or of any other organization.

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. All or any part of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive Wire articles via email, subscribe here. For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see EastWestCenter.org/Journalists.

The full list of East-West Wires produced by the Research Program is available on the East-West Center website at EastWestCenter.org/Research-Wire. For more on the East-West Center Research Program, see EastWestCenter.org/Research.

The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.

Series editors:

Derek Ferrar

[email protected]

Sidney B. Westley

[email protected]

Taxes paid and benefits received from the government are much higher in South Korea than in Indonesia, reflecting higher expenditures on public education for the young and pension and healthcare programs for the elderly.

By Andrew Mason, Sang-Hyop Lee, and Donghyun Park

HONOLULU (8 May 2020)—Elderly populations in Asia are expanding more quickly than other age groups. Low fertility rates result in fewer children and eventually fewer working-age adults, while elderly populations are living longer.

This trend began at different times in different countries and is occurring at different rates, but it is common everywhere. It has two major impacts: demand for income support for the elderly will rise because their labor income tends to be extremely low; and gross domestic product (GDP) and other aggregate economic indicators will grow more slowly as growth in the effective labor force declines and in some instances even shrinks. Policymakers across the continent face the same challenge—how to maintain economic dynamism while at the same time creating transparent and equitable mechanisms to assure some level of economic security for the elderly.

The demands for income support will be substantial. In East Asia, by 2060, more than 40 percent of the total labor income of the entire population will be needed just to fund elderly consumption beyond their own labor income. The outsized requirement for resources in East Asia stems from large elderly populations with low levels of per capita labor income and high levels of per capita consumption. In other parts of Asia, where populations are younger, elderly needs will require closer to 20 percent of total labor income.

Two sources of income for the elderly

In addition to modest labor income, resources for the elderly come from assets accumulated earlier in life and transfers from younger generations. Transfers between generations may occur within families or, increasingly, through government pensions and healthcare programs funded by tax payers. A critical challenge for policymakers is to find the right balance for old-age support by encouraging saving, supporting families, and providing a safety net of public support. Relying exclusively on just one of these options spells trouble.

Assets. Many working-age adults accumulate assets in anticipation of their retirement. They may participate in funded pension programs, buy a home, or accumulate assets in many other ways. In some countries—for example, Singapore—the accumulation of retirement assets is mandated by law.

However, to fully meet retirement needs would require massive increases in assets. In Japan by 2060, the assets required to fully fund retirement would be about eight times GDP. In China, the assets required would be less than twice GDP. Although China’s challenge would be much more modest that Japan’s, relying exclusively on assets to fund old-age needs would not be realistic in any country.

Transfers from the younger generation. Overall, family support for the elderly is increasingly giving way to the public sector. Unfortunately, just as these demands are rising, the taxes that fund government pensions and healthcare programs will have to be drawn from a declining working-age population. As labor income declines relative to needs, governments with particularly large public programs for the elderly are at greatest risk of financial stress.

Among Asian countries, the importance of public programs varies widely. In general, lower-income countries have much more modest public sectors than higher-income countries. This is illustrated by the chart comparing funds paid into the public sector (primarily taxes) and funds paid out from the public sector (including education, pensions, and healthcare, among other programs) in Indonesia and South Korea.

Although Korea’s public sector is smaller than that of many rich countries, it is much larger than Indonesia’s. As shown in the figure, at peak ages (early 40s), Koreans pay about 40 percent of their average labor income to the government, compared with about 15 percent in Indonesia.

The magnitude of government benefits also differs markedly. Public resources flowing to children are particularly high in Korea, reflecting large public investment in education. Resources flowing to the elderly are also much higher in Korea.

What are the options?

In the absence of reforms to boost economic growth or curtail the growth of retirement needs, tax revenues will rise more slowly than pension and healthcare benefits as populations age. In countries where government programs play an important role in old-age support, tax rates will have to rise more quickly or benefits will have to be curtailed or both—all options with significant political costs.

As a practical matter, the elderly rely on a combination of public transfers and saving to fund old-age needs. But which mix is best? High rates of saving, when invested productively, lead to capital accumulation and a rise in labor income. By contrast, transfers only move resources from one age group to another—there is no increase in capital or productivity.

In this respect, Asia has an advantage compared to many aging countries in Europe and Latin America. Many Asian countries rely heavily on assets rather than transfers to meet retirement consumption needs. In Japan, for example, about one-half of old-age needs are funded by assets and about one-half by transfers.Policies that promote economic growth can help ease the pressure on government budgets because people who earn more generally save more and they also pay more taxes. Investment in education and technology tends to raise worker productivity, resulting in higher earnings. Lifetime earnings are also higher in countries where young people find good-paying jobs soon after they finish school and where workers retire relatively late in life. In addition, overall labor income is higher in societies where women and older men earn salaries close to those of middle-aged men. Finally, governments need to ensure sound and transparent financial institutions that will encourage people to save for retirement. Policies such as these will contribute to both old-age economic security and economic growth.

###

Download a pdf version of this Wire article.

This East-West Wire is based on Demographic change, economic growth, and old-age economic security: Asia and the world, by Andrew Mason, Sang-Hyop Lee, and Donghyun Park. Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2020.

Andrew Mason is a Senior Fellow at the East-West Center. He can be reached at [email protected]. Sang-Hyop Lee is a Senior Fellow at the East-West Center and Professor of Economics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He can be reached at [email protected]. Donghyun Park is Principal Economist at the Asian Development Bank. He can be reached at [email protected].

The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the East-West Center or of any other organization.

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. All or any part of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive Wire articles via email, subscribe here. For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see EastWestCenter.org/Journalists.

The full list of East-West Wires produced by the Research Program is available on the East-West Center website at EastWestCenter.org/Research-Wire. For more on the East-West Center Research Program, see EastWestCenter.org/Research.

The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.

Series editors:

Derek Ferrar

[email protected]

Sidney B. Westley

[email protected]

East-West Wire

News, Commentary, and Analysis

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. Any part or all of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive East-West Center Wire media releases via email, subscribe here.

For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see www.eastwestcenter.org/journalists.