Error message

Experts Weigh In on Emerging International Policy Issues Facing the Arctic Region

HONOLULU (May 6, 2021) -- Can rival nations put aside disagreements in other parts of the world to cooperate on critical Arctic policies? Will a “precautionary management” approach help minimize the negative consequences of a warming climate for the region’s biodiversity? How can indigenous Arctic peoples be included more centrally in decision-making about the region?

These are some of the issues raised in Voices of the Future, a new series of web essays by several emerging experts who participated in the fall 2020 virtual North Pacific Arctic Conference, or NPAC, as Fellows. The annual meeting is organized by the East-West Center and supported by the Korea Maritime Institute.

"Addressing the Arctic's immense future challenges will demand the talents and dedication of a highly knowledgeable new generation of leaders," said East-West Center Adjunct Senior Fellow Nancy Lewis, who spearheaded the NPAC Fellows program. "One of the main goals of our conference is to helping to develop a diverse and inclusive cadre of such future thought leaders, and this was the inspiration behind providing younger NPAC Fellows with this special forum."

Since 2011, international officials, scholars, private sector executives, indigenous representatives and civil society leaders from a variety of countries have met annually at the East-West Center in Honolulu for wide-ranging discussions on Arctic issues, with a particular focus on the North Pacific region. This past year, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the tenth anniversary NPAC meeting to go virtual with a remote October conference on the theme “Will Great Power Politics Threaten Arctic Sustainability?” In sessions held at various times over several days, 45 participants from Northern Europe, North America, Russia, Korea, Japan, and China met online, despite sessions being held in the middle of the night in some locations.

Presentations and discussions that take place at each year’s NPAC meeting are published in a book-length volume as part of the Arctic in World Affairs series. But after the virtual 2020 conference, six of the participants also wrote special essays for the new NPAC Voices of the Future collection.

“These essays illustrate that in today’s world, ‘what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic,’” said former East-West Center President Charles E. Morrison, who chairs the NPAC Steering Committee. “Whether countries can work together to contain amplified polar climate change is of planetary significance, and the leadership must come from the North Pacific region whose countries are most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions and increased geopolitical tensions.” Topics covered in the series include:

Prospects for International Cooperation

In his article The Arctic Security Paradox, And What To Do About It, maritime dispute and resource-management expert Andreas Østhagen argues that the central question in Arctic regional relations over the last decade has been “to what degree developments in the north can be insulated from events and relationships elsewhere.” As “great-power politics,” such as the fallout from Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, have increasingly weighed on cooperative forums and venues in recent years, he writes, finding ways to address security concerns—and perhaps even develop codes of conduct—has become more urgent.

“Any Arctic security dialogue is fragile and risks being overshadowed by the increasingly tense NATO–Russia relationship in Europe at large,” Østhagen writes. “Paradoxically, it is precisely what such a dialogue would be intended to achieve—preventing the spillover of tensions from other parts of the world to the Arctic—that is the very reason why progress is difficult.”

There is no “quick fix” to security concerns in the Arctic, he concludes. Rather, “the solution is to continue to collaborate on ‘softer’ issues and recognize the complex web of arrangements that is Arctic governance. In addition, setting up a regional security forum with an inclusive and broad approach would be a much-needed confidence building measure.”

Yao Tang of China’s Polar Research Institute writes in his “Voices of the Future” essay that international cooperation in the Arctic should draw upon the spirit of the four International Polar Years that have spurred multinational research efforts since 1882—most recently in 2007-2008. “Today, too, it is important to think about how to deepen international cooperation in the Arctic through science,” he writes.

Yao cites as an example the recent Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate, or MOSAiC, joint research expedition that involved hundreds of researchers from 20 countries even amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Another example for understanding the spirit of the International Polar Year, he writes, is the Asian Forum for Polar Sciences (AFoPS), a nongovernmental organization that allows researchers from countries far from the Arctic, like Thailand and Malaysia, to participate in multinational research expeditions. “Since many countries still lack the capability to participate in Arctic international cooperation,” Yao observes, “multilateral research and logistics cooperation is of the utmost importance in the next decade.”

New Legal and Policy Frontiers

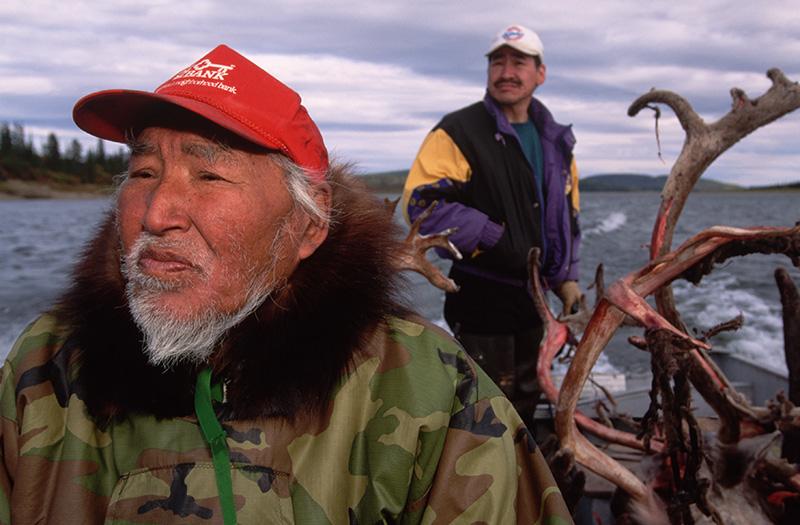

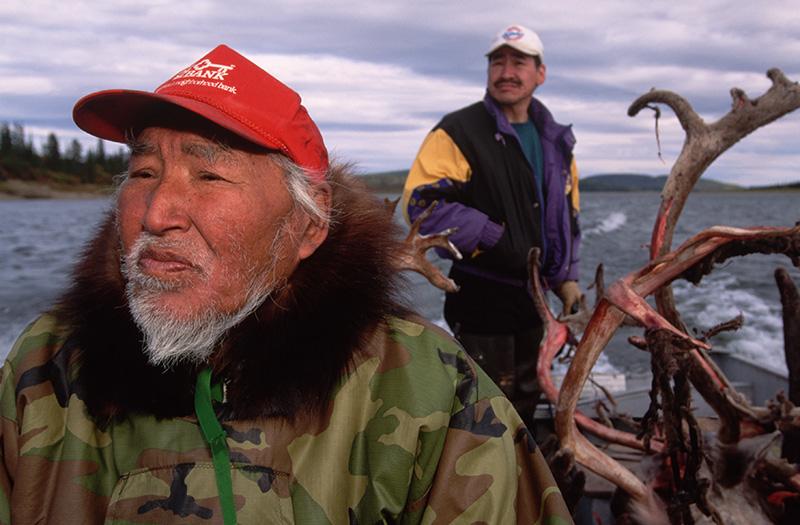

In his piece on the need to involve Indigenous Arctic communities more meaningfully in decision-making about the region, Wildlife Conservation Society ecologist Kevin Fraley writes that “centuries after first contact, Indigenous voices and governments are still not as meaningfully included in Arctic policy, management, or research decisions as they should be, despite legal consultation and inclusion requirements and the fact that the Arctic is their home.” This is becoming even more critical, he argues, as industrial development, shipping, and the effects of climate change are increasingly putting at risk the wildlife that Indigenous Arctic communities depend on for nutritional, cultural, economic, and social well-being.

Such degradation of Indigenous peoples’ food resources could even be considered a form of human rights violation, Fraley asserts, concluding that “governments, businesses, policymakers, and researchers operating in the Arctic need to ensure that Indigenous stakeholders have a voice and decision-making power at the beginning stages and throughout any policy development, industrial project, or research plan that affects their lands and food sources.”

One of the most worrisome emerging impacts of warming in the Arctic is the prospect of thawing permafrost. As ground that has been frozen solid for millennia begins to thaw, it not only releases massive amounts of greenhouse gasses, further accelerating the warming trend, but it can also undercut critical infrastructure. This was driven home dramatically by the May 2020 collapse of an oil tank near the city of Norilsk in the Russian Arctic that resulted in a major spill into the nearby Ambarnaya River.

As University of Aberdeen energy law expert Daria Shapovalova writes in her piece How Thawing Permafrost Challenges Environmental Governance, the phenomenon also raises a whole new frontier of law and policy. “It is clear that in the rapidly warming Arctic the thawing permafrost presents challenges that will require large financial commitments and comprehensive, inclusive approaches,” she writes. “Yet responsibilities for adaptation and liability for any potential damage of permafrost thaw are not well-defined either in international or Arctic States’ law.”

While international bodies like the Arctic Council are useful for high-level discussion, Shapovalova argues, the relevant policies will need to be adopted at the national level to address local conditions. “In particular,” she writes, “there is a need to ensure that any new projects consider longer-term warming effects and potential permafrost disintegration.”

Another emerging arena in Arctic policy, writes Queen’s University PHD candidate in international law Ekaterina Antsygina, is the relatively recent phenomenon of countries in the region defining the defining the outer limits of their extended continental shelf, as allowed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The vast extended continental shelf, or ECS, entitlements asserted by Russia, Denmark, and Canada in the Central Arctic Ocean, she explains, mean that when the process plays out those three nations will be dividing up continental shelves in the heart of the Arctic.

‘Precautionary Management’

Once the Arctic’s intricate natural systems pass certain tipping points it might be too late to fix the damage, Yunjin Kim writes in her essay Warming Arctic Requires ‘Precautionary Management’ Approach. “In such circumstances,” she asserts, “the success of future marine cooperation in the Arctic Ocean calls for precautionary action to minimize the impact of environmental concerns at an international level.”

This approach would call on governments to base their Arctic decisions and actions on careful foresight when their activities may be expected to cause damage to the changing Arctic marine environment. Consequently, argues Kim, a former researcher with the Korea Legislation Research Institute, “nations should recognize their common interest preventing transboundary environmental harm in the Arctic Ocean in order to avoid the more difficult task of curing problems after they have occurred.”

Top Photo: An Inuit man gives his sled dogs a rest while looking over newly melted sea ice exposing the Arctic ocean. Credit: Justin Lewis/Getty Images

Experts Weigh In on Emerging International Policy Issues Facing the Arctic Region

HONOLULU (May 6, 2021) -- Can rival nations put aside disagreements in other parts of the world to cooperate on critical Arctic policies? Will a “precautionary management” approach help minimize the negative consequences of a warming climate for the region’s biodiversity? How can indigenous Arctic peoples be included more centrally in decision-making about the region?

These are some of the issues raised in Voices of the Future, a new series of web essays by several emerging experts who participated in the fall 2020 virtual North Pacific Arctic Conference, or NPAC, as Fellows. The annual meeting is organized by the East-West Center and supported by the Korea Maritime Institute.

"Addressing the Arctic's immense future challenges will demand the talents and dedication of a highly knowledgeable new generation of leaders," said East-West Center Adjunct Senior Fellow Nancy Lewis, who spearheaded the NPAC Fellows program. "One of the main goals of our conference is to helping to develop a diverse and inclusive cadre of such future thought leaders, and this was the inspiration behind providing younger NPAC Fellows with this special forum."

Since 2011, international officials, scholars, private sector executives, indigenous representatives and civil society leaders from a variety of countries have met annually at the East-West Center in Honolulu for wide-ranging discussions on Arctic issues, with a particular focus on the North Pacific region. This past year, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the tenth anniversary NPAC meeting to go virtual with a remote October conference on the theme “Will Great Power Politics Threaten Arctic Sustainability?” In sessions held at various times over several days, 45 participants from Northern Europe, North America, Russia, Korea, Japan, and China met online, despite sessions being held in the middle of the night in some locations.

Presentations and discussions that take place at each year’s NPAC meeting are published in a book-length volume as part of the Arctic in World Affairs series. But after the virtual 2020 conference, six of the participants also wrote special essays for the new NPAC Voices of the Future collection.

“These essays illustrate that in today’s world, ‘what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic,’” said former East-West Center President Charles E. Morrison, who chairs the NPAC Steering Committee. “Whether countries can work together to contain amplified polar climate change is of planetary significance, and the leadership must come from the North Pacific region whose countries are most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions and increased geopolitical tensions.” Topics covered in the series include:

Prospects for International Cooperation

In his article The Arctic Security Paradox, And What To Do About It, maritime dispute and resource-management expert Andreas Østhagen argues that the central question in Arctic regional relations over the last decade has been “to what degree developments in the north can be insulated from events and relationships elsewhere.” As “great-power politics,” such as the fallout from Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, have increasingly weighed on cooperative forums and venues in recent years, he writes, finding ways to address security concerns—and perhaps even develop codes of conduct—has become more urgent.

“Any Arctic security dialogue is fragile and risks being overshadowed by the increasingly tense NATO–Russia relationship in Europe at large,” Østhagen writes. “Paradoxically, it is precisely what such a dialogue would be intended to achieve—preventing the spillover of tensions from other parts of the world to the Arctic—that is the very reason why progress is difficult.”

There is no “quick fix” to security concerns in the Arctic, he concludes. Rather, “the solution is to continue to collaborate on ‘softer’ issues and recognize the complex web of arrangements that is Arctic governance. In addition, setting up a regional security forum with an inclusive and broad approach would be a much-needed confidence building measure.”

Yao Tang of China’s Polar Research Institute writes in his “Voices of the Future” essay that international cooperation in the Arctic should draw upon the spirit of the four International Polar Years that have spurred multinational research efforts since 1882—most recently in 2007-2008. “Today, too, it is important to think about how to deepen international cooperation in the Arctic through science,” he writes.

Yao cites as an example the recent Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate, or MOSAiC, joint research expedition that involved hundreds of researchers from 20 countries even amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Another example for understanding the spirit of the International Polar Year, he writes, is the Asian Forum for Polar Sciences (AFoPS), a nongovernmental organization that allows researchers from countries far from the Arctic, like Thailand and Malaysia, to participate in multinational research expeditions. “Since many countries still lack the capability to participate in Arctic international cooperation,” Yao observes, “multilateral research and logistics cooperation is of the utmost importance in the next decade.”

New Legal and Policy Frontiers

In his piece on the need to involve Indigenous Arctic communities more meaningfully in decision-making about the region, Wildlife Conservation Society ecologist Kevin Fraley writes that “centuries after first contact, Indigenous voices and governments are still not as meaningfully included in Arctic policy, management, or research decisions as they should be, despite legal consultation and inclusion requirements and the fact that the Arctic is their home.” This is becoming even more critical, he argues, as industrial development, shipping, and the effects of climate change are increasingly putting at risk the wildlife that Indigenous Arctic communities depend on for nutritional, cultural, economic, and social well-being.

Such degradation of Indigenous peoples’ food resources could even be considered a form of human rights violation, Fraley asserts, concluding that “governments, businesses, policymakers, and researchers operating in the Arctic need to ensure that Indigenous stakeholders have a voice and decision-making power at the beginning stages and throughout any policy development, industrial project, or research plan that affects their lands and food sources.”

One of the most worrisome emerging impacts of warming in the Arctic is the prospect of thawing permafrost. As ground that has been frozen solid for millennia begins to thaw, it not only releases massive amounts of greenhouse gasses, further accelerating the warming trend, but it can also undercut critical infrastructure. This was driven home dramatically by the May 2020 collapse of an oil tank near the city of Norilsk in the Russian Arctic that resulted in a major spill into the nearby Ambarnaya River.

As University of Aberdeen energy law expert Daria Shapovalova writes in her piece How Thawing Permafrost Challenges Environmental Governance, the phenomenon also raises a whole new frontier of law and policy. “It is clear that in the rapidly warming Arctic the thawing permafrost presents challenges that will require large financial commitments and comprehensive, inclusive approaches,” she writes. “Yet responsibilities for adaptation and liability for any potential damage of permafrost thaw are not well-defined either in international or Arctic States’ law.”

While international bodies like the Arctic Council are useful for high-level discussion, Shapovalova argues, the relevant policies will need to be adopted at the national level to address local conditions. “In particular,” she writes, “there is a need to ensure that any new projects consider longer-term warming effects and potential permafrost disintegration.”

Another emerging arena in Arctic policy, writes Queen’s University PHD candidate in international law Ekaterina Antsygina, is the relatively recent phenomenon of countries in the region defining the defining the outer limits of their extended continental shelf, as allowed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The vast extended continental shelf, or ECS, entitlements asserted by Russia, Denmark, and Canada in the Central Arctic Ocean, she explains, mean that when the process plays out those three nations will be dividing up continental shelves in the heart of the Arctic.

‘Precautionary Management’

Once the Arctic’s intricate natural systems pass certain tipping points it might be too late to fix the damage, Yunjin Kim writes in her essay Warming Arctic Requires ‘Precautionary Management’ Approach. “In such circumstances,” she asserts, “the success of future marine cooperation in the Arctic Ocean calls for precautionary action to minimize the impact of environmental concerns at an international level.”

This approach would call on governments to base their Arctic decisions and actions on careful foresight when their activities may be expected to cause damage to the changing Arctic marine environment. Consequently, argues Kim, a former researcher with the Korea Legislation Research Institute, “nations should recognize their common interest preventing transboundary environmental harm in the Arctic Ocean in order to avoid the more difficult task of curing problems after they have occurred.”

Top Photo: An Inuit man gives his sled dogs a rest while looking over newly melted sea ice exposing the Arctic ocean. Credit: Justin Lewis/Getty Images

East-West Wire

News, Commentary, and Analysis

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. Any part or all of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive East-West Center Wire media releases via email, subscribe here.

For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see www.eastwestcenter.org/journalists.