Error message

By Kevin Fraley

Fisheries Ecologist, Arctic Beringia Program, Wildlife Conservation Society

kfraley@wcs.org

Posted April 23, 2021

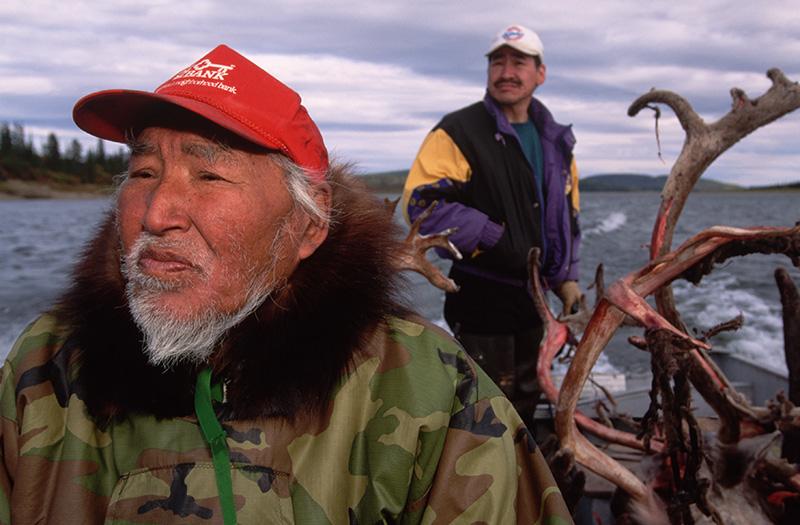

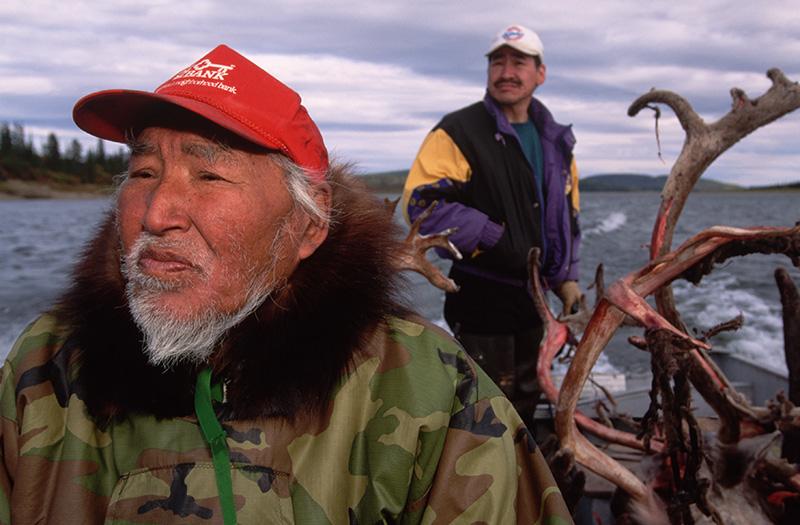

Despite having strong voices and being conscientious stewards of the environment, wildlife, and fishes that they depend upon for food security and cultural identity (Reed et al. 2020; see Figure 1), Indigenous peoples in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic have been and continue to be marginalized in management and policy discussions.

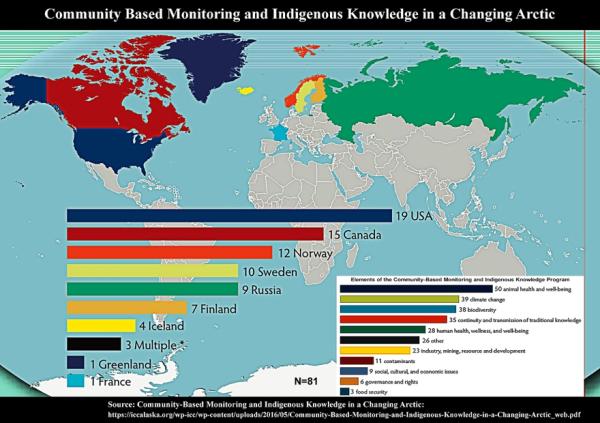

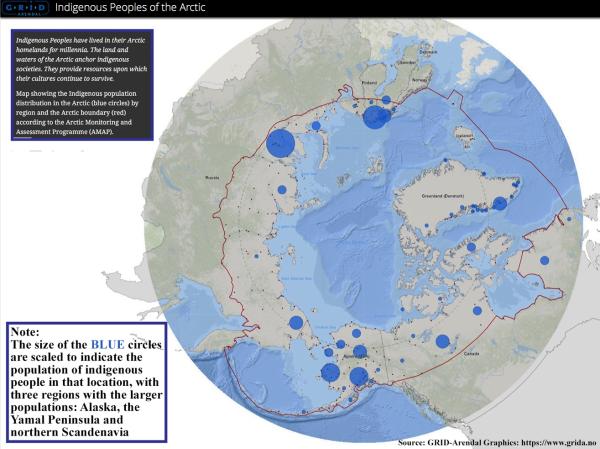

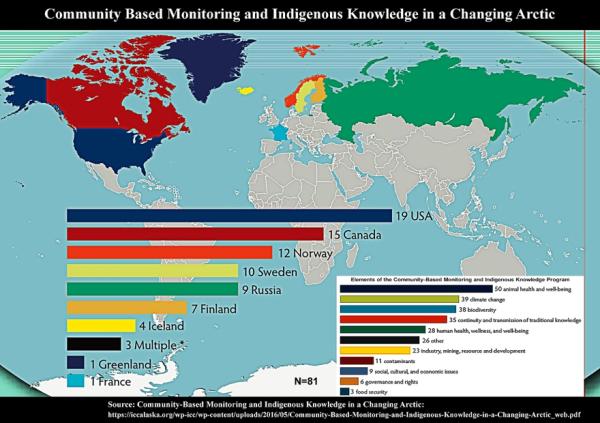

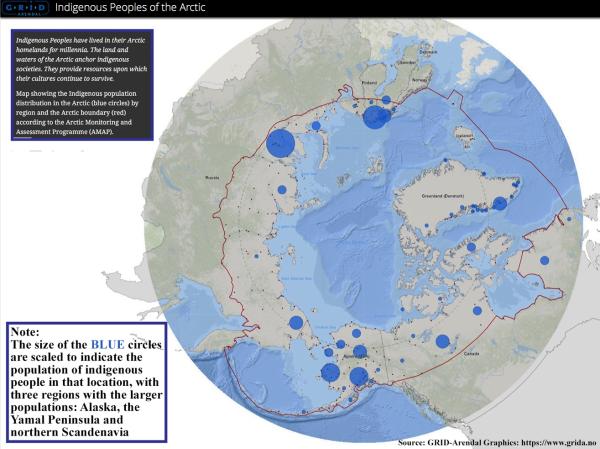

The history of Western first contact and interactions with Alaska Native Peoples and Canada’s First Nations is well documented (CSPN 1999), with many tragedies but some shining examples of cooperation. However, centuries after first contact, Indigenous voices and governments are still not as meaningfully included in Arctic policy, management, or research decisions as they should be, despite legal consultation and inclusion requirements and the fact that the Arctic is their home (Figure 2).

Additionally, as industrial development, shipping, and the effects of climate change become more prevalent in the Arctic, the wildlife, fish, and flora that Indigenous communities depend on for nutritional, cultural, economic, and social wellbeing are increasingly at risk (ICC-A 2015). Given the current “total environment of change” (Moerlein and Carothers 2012), Indigenous stakeholder involvement and food security is simultaneously an emerging issue in the Arctic, due to the recent upswell in the acknowledgement of Indigenous rights, and also a venerable one (Etty et al. 2020).

History of exclusion

Dating back to the beginning of contact with Indigenous communities in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic, Western leaders and governments have often neglected to consult in earnest with Indigenous governments when planning or executing major policy changes or industrial development that profoundly affect these peoples. Indigenous groups have led many successful protests against this neglect, such as the Utqiaġvik duck hunting closure protests and activism against the Project Chariot nuclear harbor plan (O’Neill 1994; Burwell 2005).

Indigenous and rural residents are the groups most affected by Arctic policy and management decisions, yet they often are not included at the ground level of new projects. There is a social mandate to involve and protect the people who call the Arctic home, because they are the ones most vulnerable to changes there. To adapt the words of a common saying, “the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most [marginalized] members.”

Photo: Peter Guttman/Getty Images.

Current examples

There are a number of current examples of failure to involve Arctic Indigenous communities in decision-making that affects their food security. The Ambler Road Industrial Project, which would cut across more than 200 miles of de facto wilderness and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve in Alaska, is opposed by the majority of the tribal governments and people of the villages that this project will affect (BLM 2020). Yet, the right-of-way for the road was permitted in July 2020, resulting in lawsuits being brought against the US federal government by both tribes and environmental groups (DeMarban 2020a).

This road would expose inconnu, Pacific salmon, and northern pike populations in the Kobuk River, which Indigenous and rural Alaskans depend upon for sustenance, to potential oil spills, bio-accumulative contaminants, and exploitation. However, the input of tribal groups was completely ignored in favor of development.

Additionally, drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge of Alaska is a deeply unpopular initiative (Leiserowitz et al. 2019) that is opposed by the majority of Americans and many tribal groups, including the Gwich’in Nation, because of possible negative impacts on the Porcupine caribou herd, which Gwich’in and Iñupiaq communities depend upon for food (BLM 2019). Despite this opposition, the US federal government has moved forward with oil lease sales in the Refuge (DeMarban 2020b), ignoring public opinion and the will of tribal governments and villages.

Even in the realm of scientific research, the perspectives of Indigenous communities are not often solicited. Researchers commonly attempt to garner support for their projects from tribal organizations at the last minute, after research planning has already been completed (ACVP 2020). Given these examples, it is clear that Indigenous voices are still being ignored and their food security threatened, despite the well-known blunders of the past (e.g., the Katie John subsistence fishing cases or Utqiaġvik duck hunting closure controversy; Burwell 2005, Anderson 2016).

Effects of development make food security urgent

As we continue to uncover the effects of industrial development and climate change in the Arctic, the issue of Indigenous and rural Arctic residents’ food security will become more urgent (ICC-A 2015; Stepien et al. 2014). Such effects include disruption of animal migrations, deposition and bioaccumulation of contaminants (e.g., per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) in animals harvested for subsistence, die-offs of marine mammals, fish mortality caused by warming waters and disease, and mercurial weather and ice conditions that make harvesting wild foods more difficult (Van Oostdam et al. 2005; Burek et al. 2008; Huntington et al. 2016; Sformo et al. 2017).

Already, coastal erosion threatens the very existence of communities like Niugtaq (Newtok), Alaska, and poor salmon returns on the Yukon River are leaving villagers short on salmon to feed themselves and their sled dogs. The concerns are especially acute if industrial development and shipping continue to increase as expected or if commercial fisheries expand into the Arctic, because these developments could trigger cascading ecological impacts on species of subsistence importance (Ghosh and Rubly 2015).

Treating food resources as human rights

Degradation of the food resources of Indigenous peoples, when policymakers and the public are aware of what is happening but are not proactive in combatting the impacts, could be considered a type of human rights violation (FAO 2008; Nakashima et al. 2018). Therefore, governments, businesses, policymakers, and researchers operating in the Arctic need to ensure that Indigenous stakeholders have a voice and decision-making power in the beginning stages and throughout any policy development, industrial project, or research plan that affects their lands and food sources.

With growing awareness among the general public, recent social trends support increased Indigenous rights and acknowledgement, boosted by the high-profile protests around the Dakota Access Pipeline, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge drilling project, and Black Lives Matter movement in the United States. But this change in mindset has yet to translate to policy, legislation, or decision-making arenas (Etty et al. 2020). Encouraging the involvement and power of Indigenous stakeholders will promote social responsibility and decrease the likelihood of degradation of important subsistence and cultural resources, as we move into the future of the Arctic.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of the East-West Center or of any other organization.

References

Alaska Council of Village Presidents (ACVP), Kawerak, Inc., Bering Sea Elders Group, Aleut Community of St. Paul. 2020. Letter to National Science Foundation, Navigating the New Arctic Program. March 19, 2020.

Anderson, R. T. 2016. Sovereignty and subsistence: Native self-government and rights to hunt, fish, and gather after ANCSA. Alaska Law Review 33: 187–227. URL: https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/alr/vol33/iss2/3

Burek, K. A., Gulland, F. M., & O'Hara, T. M. (2008). Effects of climate change on Arctic marine mammal health. Ecological Applications 18(sp2): S126–S134.

Burwell, M. (2005, March). Hunger knows no law: seminal native protest and the Barrow Duck-In of 1961. In Conference paper delivered to the Arctic Division AAAS Annual Meeting. Anchorage (AK).

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest (CSPN). (1999). Indians and Europeans on the Northwest Coast: Historical Context: https://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Classroom%20Materials/Curriculum%20Packets/Indians%20&%20Europeans/II.html

DeMarban, A. (2020a) Villages sue Trump administration over proposed mining road that would cut through remote Interior Alaska. Anchorage Daily News. October 7, 2020.

DeMarban, A. (2020b) Trump administration schedules Arctic Alaska refuge oil and gas lease sale for early January. Anchorage Daily News. December 3, 2020.

Etty, T., Heyvaert, V., Carlarne, C., Huber, B., Peel, J., & van Zeben, J. (2020). Indigenous Rights Amidst Global Turmoil, Transnational Environmental Law 9(3): 385–391.

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. 2008. The Right to Food and Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/Right_to_food.pdf

Ghosh, S., & Rubly, C. (2015). The emergence of Arctic shipping: issues, threats, costs, and risk-mitigating strategies of the Polar Code. Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 7(3): 171–182.

Huntington, H. P., Quakenbush, L. T., & Nelson, M. (2016). Effects of changing sea ice on marine mammals and subsistence hunters in northern Alaska from traditional knowledge interviews. Biology Letters 12(8): 20160198.

Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska (ICC-A) (2015) Alaskan Inuit food security conceptual framework: How to assess the Arctic from an Inuit perspective. Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska, Anchorage, Alaska, USA.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., Ballew, M., Goldberg, M., Gustafson, A., & Bergquist, P. (2019). Politics & Global Warming. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/NBJGS

Moerlein, K. J., & Carothers, C. (2012). Total environment of change: Impacts of climate change and social transitions on subsistence fisheries in northwest Alaska. Ecology and Society 17(1): pp.

Nakashima, D., Krupnik, I., & Rubis, J. T. (eds.). (2018). Indigenous knowledge for climate change assessment and adaptation. Cambridge University Press.

O'Neill, D. 1994. The firecracker boys: H-bombs, Inupiat Eskimos, and the roots of the environmental movement. Basic Books, New York.

Reed, G., Brunet, N. D., Longboat, S., & Natcher, D. C. (2020). Indigenous guardians as an emerging approach to indigenous environmental governance. Conservation Biology

Sformo, T.L., Adams, B., Seigle, J.C., Ferguson, J.A., Purcell, M.K., Stimmelmayr, R., et al. (2017).

Observations and first reports of saprolegniosis in Aanaakłiq, broad whitefish (Coregonus nasus), from the Colville River near Nuiqsut, Alaska. Polar Science 14: 78–82.

Stepien, A., Koivurova, T., Gremsperger, A., & Niemi, H. (2014). Arctic indigenous peoples and the challenge of climate change. In Arctic Marine Governance (pp. 71–99). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) (2020) Ambler Road Environmental Impact Statement Volume 1: Chapters 1–3, Appendices A–F. Fairbanks, Alaska.

U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) (2019) Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program Environmental Impact Statement. Fairbanks, Alaska.

Van Oostdam, J., Donaldson, S. G., Feeley, M., Arnold, D., Ayotte, P., Bondy, G., ... & Loring, E. (2005). Human health implications of environmental contaminants in Arctic Canada: A review. Science of the Total Environment 351: 165–246.

By Kevin Fraley

Fisheries Ecologist, Arctic Beringia Program, Wildlife Conservation Society

kfraley@wcs.org

Posted April 23, 2021

Despite having strong voices and being conscientious stewards of the environment, wildlife, and fishes that they depend upon for food security and cultural identity (Reed et al. 2020; see Figure 1), Indigenous peoples in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic have been and continue to be marginalized in management and policy discussions.

The history of Western first contact and interactions with Alaska Native Peoples and Canada’s First Nations is well documented (CSPN 1999), with many tragedies but some shining examples of cooperation. However, centuries after first contact, Indigenous voices and governments are still not as meaningfully included in Arctic policy, management, or research decisions as they should be, despite legal consultation and inclusion requirements and the fact that the Arctic is their home (Figure 2).

Additionally, as industrial development, shipping, and the effects of climate change become more prevalent in the Arctic, the wildlife, fish, and flora that Indigenous communities depend on for nutritional, cultural, economic, and social wellbeing are increasingly at risk (ICC-A 2015). Given the current “total environment of change” (Moerlein and Carothers 2012), Indigenous stakeholder involvement and food security is simultaneously an emerging issue in the Arctic, due to the recent upswell in the acknowledgement of Indigenous rights, and also a venerable one (Etty et al. 2020).

History of exclusion

Dating back to the beginning of contact with Indigenous communities in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic, Western leaders and governments have often neglected to consult in earnest with Indigenous governments when planning or executing major policy changes or industrial development that profoundly affect these peoples. Indigenous groups have led many successful protests against this neglect, such as the Utqiaġvik duck hunting closure protests and activism against the Project Chariot nuclear harbor plan (O’Neill 1994; Burwell 2005).

Indigenous and rural residents are the groups most affected by Arctic policy and management decisions, yet they often are not included at the ground level of new projects. There is a social mandate to involve and protect the people who call the Arctic home, because they are the ones most vulnerable to changes there. To adapt the words of a common saying, “the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most [marginalized] members.”

Photo: Peter Guttman/Getty Images.

Current examples

There are a number of current examples of failure to involve Arctic Indigenous communities in decision-making that affects their food security. The Ambler Road Industrial Project, which would cut across more than 200 miles of de facto wilderness and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve in Alaska, is opposed by the majority of the tribal governments and people of the villages that this project will affect (BLM 2020). Yet, the right-of-way for the road was permitted in July 2020, resulting in lawsuits being brought against the US federal government by both tribes and environmental groups (DeMarban 2020a).

This road would expose inconnu, Pacific salmon, and northern pike populations in the Kobuk River, which Indigenous and rural Alaskans depend upon for sustenance, to potential oil spills, bio-accumulative contaminants, and exploitation. However, the input of tribal groups was completely ignored in favor of development.

Additionally, drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge of Alaska is a deeply unpopular initiative (Leiserowitz et al. 2019) that is opposed by the majority of Americans and many tribal groups, including the Gwich’in Nation, because of possible negative impacts on the Porcupine caribou herd, which Gwich’in and Iñupiaq communities depend upon for food (BLM 2019). Despite this opposition, the US federal government has moved forward with oil lease sales in the Refuge (DeMarban 2020b), ignoring public opinion and the will of tribal governments and villages.

Even in the realm of scientific research, the perspectives of Indigenous communities are not often solicited. Researchers commonly attempt to garner support for their projects from tribal organizations at the last minute, after research planning has already been completed (ACVP 2020). Given these examples, it is clear that Indigenous voices are still being ignored and their food security threatened, despite the well-known blunders of the past (e.g., the Katie John subsistence fishing cases or Utqiaġvik duck hunting closure controversy; Burwell 2005, Anderson 2016).

Effects of development make food security urgent

As we continue to uncover the effects of industrial development and climate change in the Arctic, the issue of Indigenous and rural Arctic residents’ food security will become more urgent (ICC-A 2015; Stepien et al. 2014). Such effects include disruption of animal migrations, deposition and bioaccumulation of contaminants (e.g., per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) in animals harvested for subsistence, die-offs of marine mammals, fish mortality caused by warming waters and disease, and mercurial weather and ice conditions that make harvesting wild foods more difficult (Van Oostdam et al. 2005; Burek et al. 2008; Huntington et al. 2016; Sformo et al. 2017).

Already, coastal erosion threatens the very existence of communities like Niugtaq (Newtok), Alaska, and poor salmon returns on the Yukon River are leaving villagers short on salmon to feed themselves and their sled dogs. The concerns are especially acute if industrial development and shipping continue to increase as expected or if commercial fisheries expand into the Arctic, because these developments could trigger cascading ecological impacts on species of subsistence importance (Ghosh and Rubly 2015).

Treating food resources as human rights

Degradation of the food resources of Indigenous peoples, when policymakers and the public are aware of what is happening but are not proactive in combatting the impacts, could be considered a type of human rights violation (FAO 2008; Nakashima et al. 2018). Therefore, governments, businesses, policymakers, and researchers operating in the Arctic need to ensure that Indigenous stakeholders have a voice and decision-making power in the beginning stages and throughout any policy development, industrial project, or research plan that affects their lands and food sources.

With growing awareness among the general public, recent social trends support increased Indigenous rights and acknowledgement, boosted by the high-profile protests around the Dakota Access Pipeline, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge drilling project, and Black Lives Matter movement in the United States. But this change in mindset has yet to translate to policy, legislation, or decision-making arenas (Etty et al. 2020). Encouraging the involvement and power of Indigenous stakeholders will promote social responsibility and decrease the likelihood of degradation of important subsistence and cultural resources, as we move into the future of the Arctic.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of the East-West Center or of any other organization.

References

Alaska Council of Village Presidents (ACVP), Kawerak, Inc., Bering Sea Elders Group, Aleut Community of St. Paul. 2020. Letter to National Science Foundation, Navigating the New Arctic Program. March 19, 2020.

Anderson, R. T. 2016. Sovereignty and subsistence: Native self-government and rights to hunt, fish, and gather after ANCSA. Alaska Law Review 33: 187–227. URL: https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/alr/vol33/iss2/3

Burek, K. A., Gulland, F. M., & O'Hara, T. M. (2008). Effects of climate change on Arctic marine mammal health. Ecological Applications 18(sp2): S126–S134.

Burwell, M. (2005, March). Hunger knows no law: seminal native protest and the Barrow Duck-In of 1961. In Conference paper delivered to the Arctic Division AAAS Annual Meeting. Anchorage (AK).

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest (CSPN). (1999). Indians and Europeans on the Northwest Coast: Historical Context: https://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Classroom%20Materials/Curriculum%20Packets/Indians%20&%20Europeans/II.html

DeMarban, A. (2020a) Villages sue Trump administration over proposed mining road that would cut through remote Interior Alaska. Anchorage Daily News. October 7, 2020.

DeMarban, A. (2020b) Trump administration schedules Arctic Alaska refuge oil and gas lease sale for early January. Anchorage Daily News. December 3, 2020.

Etty, T., Heyvaert, V., Carlarne, C., Huber, B., Peel, J., & van Zeben, J. (2020). Indigenous Rights Amidst Global Turmoil, Transnational Environmental Law 9(3): 385–391.

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. 2008. The Right to Food and Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/Right_to_food.pdf

Ghosh, S., & Rubly, C. (2015). The emergence of Arctic shipping: issues, threats, costs, and risk-mitigating strategies of the Polar Code. Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs 7(3): 171–182.

Huntington, H. P., Quakenbush, L. T., & Nelson, M. (2016). Effects of changing sea ice on marine mammals and subsistence hunters in northern Alaska from traditional knowledge interviews. Biology Letters 12(8): 20160198.

Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska (ICC-A) (2015) Alaskan Inuit food security conceptual framework: How to assess the Arctic from an Inuit perspective. Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska, Anchorage, Alaska, USA.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., Ballew, M., Goldberg, M., Gustafson, A., & Bergquist, P. (2019). Politics & Global Warming. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/NBJGS

Moerlein, K. J., & Carothers, C. (2012). Total environment of change: Impacts of climate change and social transitions on subsistence fisheries in northwest Alaska. Ecology and Society 17(1): pp.

Nakashima, D., Krupnik, I., & Rubis, J. T. (eds.). (2018). Indigenous knowledge for climate change assessment and adaptation. Cambridge University Press.

O'Neill, D. 1994. The firecracker boys: H-bombs, Inupiat Eskimos, and the roots of the environmental movement. Basic Books, New York.

Reed, G., Brunet, N. D., Longboat, S., & Natcher, D. C. (2020). Indigenous guardians as an emerging approach to indigenous environmental governance. Conservation Biology

Sformo, T.L., Adams, B., Seigle, J.C., Ferguson, J.A., Purcell, M.K., Stimmelmayr, R., et al. (2017).

Observations and first reports of saprolegniosis in Aanaakłiq, broad whitefish (Coregonus nasus), from the Colville River near Nuiqsut, Alaska. Polar Science 14: 78–82.

Stepien, A., Koivurova, T., Gremsperger, A., & Niemi, H. (2014). Arctic indigenous peoples and the challenge of climate change. In Arctic Marine Governance (pp. 71–99). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) (2020) Ambler Road Environmental Impact Statement Volume 1: Chapters 1–3, Appendices A–F. Fairbanks, Alaska.

U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) (2019) Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program Environmental Impact Statement. Fairbanks, Alaska.

Van Oostdam, J., Donaldson, S. G., Feeley, M., Arnold, D., Ayotte, P., Bondy, G., ... & Loring, E. (2005). Human health implications of environmental contaminants in Arctic Canada: A review. Science of the Total Environment 351: 165–246.