Error message

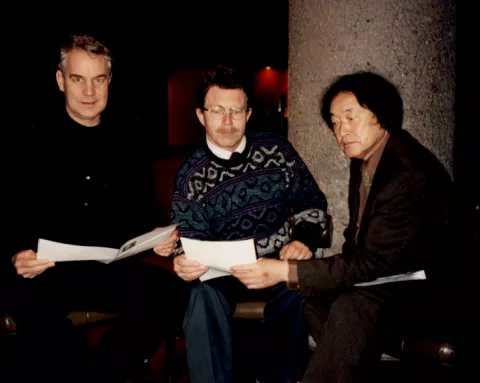

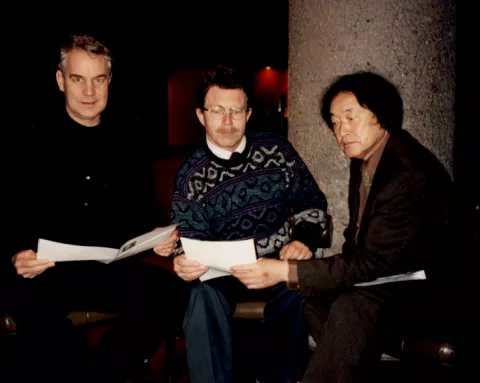

Tsugaru shamisen presentation at the Polynesian Cultural Center, 1999

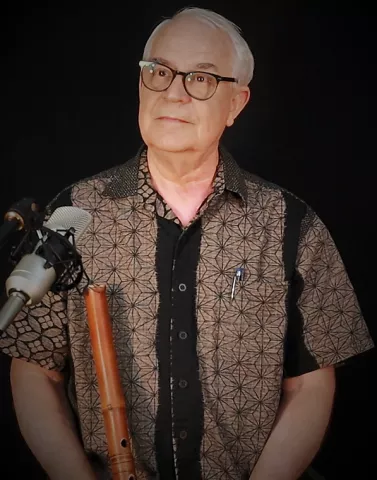

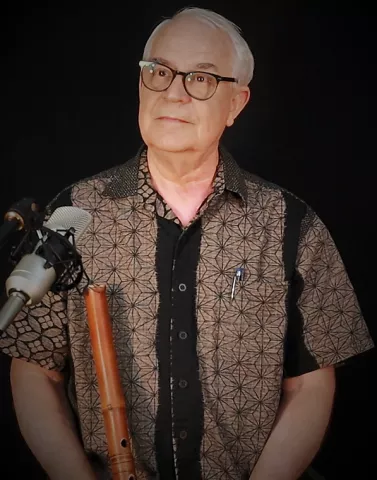

Christopher Yohmei Blasdel

Tsugaru shamisen, vocal and dance group at Chatham College, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Humans of EWC offers a window into our community for those interested in learning about the East-West Center through a more personal lens. The feature below includes extended materials from our Humans interview with Christopher Blasdel, accomplished shakuhachi performer, music professor, and EWC Arts Program resource.

Interview Transcript

Today we're featuring Professor Christopher Blasdel, a long-time resource for the EWC Arts Program. Professor Blasdel, would you like to introduce yourself?

My name is Christopher Blasdel. I perform the shakuhachi, which is the traditional bamboo flute of Japan. I’ve done this for about 50 years now. And I perform under a performing name, Christopher Yohmei.

And in what capacity have you been connected with the Center?

I have been involved with the East-West Center since around the late 1980s, doing a number of very interesting programs with them, including Asian music, of course Japanese music, fusion, and various collaborations.

My official status at the East-West Center is that of an alumnus. I’ve been here many times for programs, workshops, performances, lectures — I was put onto their mailing list as someone of value to and connected with the Center.

How did you first become involved with the Center, and the Arts Program specifically?

I first heard of the East-West Center back in 1968 or 1969, when my former sister-in-law attended a summer session there. I was in high school at the time, and the East-West Center seemed very magical to me, mostly because it was in Hawai‘i, whereas I grew up in the flat, waterless plains of Texas.

My connection with the Center dates back to the 1980s, when I was living in Japan—I lived there from 1972 to 2016. At the time I was working as a performer, and teacher and also the Artistic Director at the International House of Japan. It was through that connection where I met Bill Feltz, the former director of the Arts Program at the East-West Center. And he was the first one who arranged my performance at the Center, which, of course, involved Japanese music. Bill was a student of Japanese music (he studied koto) and had spent time in Japan, and had a huge appreciation and interest in Japanese music.

Was there any defining moment or activity in your history and affiliation with the Center that stands out as representative of the ethos of this place as you understood it?

What I liked about Bill and his approach, and also, I realized later, constituted the basic stance of the East-West Center, was that he encouraged collaboration and outreach. He also encouraged collaborative performances between people who normally wouldn’t have the chance to play together. For example, I remember in particular one program that Bill created: a concert tour of Tsugaru shamisen, which is a northern folk shamisen tradition with very powerful performance styles and expressive singing. Tsugaru shamisen is very popular in Japan and around the world now. Bill arranged for a master shamisen player and his students, along with the master’s wife who is a singer, to do a concert tour of the United States mainland and also Hawai‘i. And here I was, as a non-Japanese, thrown into the mix, and my forte was not even folk music, but I was able to learn the style quite quickly through the help of these masters who came from Aomori, from the north part of Japan. And it was an opportunity I would never have had just on my own. It was through the interest and the focus and the generosity of the East-West Center and Bill’s avid interest in Japanese music and sharing that with a lot of people that I was able to join, take part and hopefully have made a contribution to the concert tour.

Can you tell us a little more about your musical background? Where did you study? How did you get to where you are now?

My formal musical training started in a local band in Texas playing trombone. My father played trombone and I used his old instrument. I played it in the high school marching and concert band, which was fun. And then I decided, well, the trombone is really too big to easily carry around, so I’ll switch to flute. My mother had a flute, so I started playing it. During my junior year at college I went to Japan for a foreign year abroad program, thinking I should learn some sort of Japanese flute.

There are a number of traditional flutes utilized in Japanese music, like the ryūteki and shinobue, but of all these flutes, the shakuhachi appealed to me. What was meaningful to me about the shakuhachi was its relationship to the Buddhist tradition and the overall spiritual culture of Japan. And I loved the fact that the shakuhachi is so simply made–it has only five holes, but with those five holes you can produce a variety of tones and melodies. The shakuhachi is a very limited instrument, but within those limitations you have this great expanse of possibilities. And that’s what I liked about it. It’s not complicated, it’s very simple. It’s just a piece of bamboo with five holes in it. You blow into it. But that’s where the difficult part starts. How do you blow into it? How do you create a sound? How do you create nuance and tone that can reach out and really grab your audience? And that’s what I found so fascinating and interesting about the shakuhachi.

And then later on, I got into the graduate school of the University of Fine Arts in Tokyo (Geidai), and studied gagaku with people like the ryūteki master Shiba Sensei, and of course my shakuhachi teacher, Yamuguchi Goro, along with many other wonderful teachers whom I never would have never had the chance to study with if I wasn’t in Japan at that time.

And beyond studying with them, you eventually worked collaboratively with these teachers as a fellow performer on stage. Is that correct?

It turned out that the ryūteki master Shiba sensei was also interested in contemporary music, including improvisation. So for one of my recitals I asked him to join me—here I was, this young student asking his master to perform with me–not something that happens often in the world of traditional Japanese music. I had quite the chutzpah back then! But he agreed, and I got the feeling he loved the idea, as it was something he didn’t get to do very often as a court musician. We came up with this co-improvised song called “The Night of the Garuda.” Garuda is the mythical bird of Indonesia, also ubiquitous in Thailand, that has a gigantic wingspan and eats dragons. The Garuda can symbolize many things, but to me this regal, dragon-eating bird was something I wanted to express with the music of the shakuhachi and ryūteki. The timbres of these instruments have both similarities and differences, but they seem to fit together well. As Shiba sensei is now passed, I feel it was a huge honor to have been able to work with him.

To hear “Night of the Garuda,” featuring Professor Christopher Yohmei Blasdel and Shiba sensei, please see the video below.

You can also hear more of Professor Christopher Blasdel's story and performances at his website https://www.yohmei.com/.

Tsugaru shamisen presentation at the Polynesian Cultural Center, 1999

Christopher Yohmei Blasdel

Tsugaru shamisen, vocal and dance group at Chatham College, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Humans of EWC offers a window into our community for those interested in learning about the East-West Center through a more personal lens. The feature below includes extended materials from our Humans interview with Christopher Blasdel, accomplished shakuhachi performer, music professor, and EWC Arts Program resource.

Interview Transcript

Today we're featuring Professor Christopher Blasdel, a long-time resource for the EWC Arts Program. Professor Blasdel, would you like to introduce yourself?

My name is Christopher Blasdel. I perform the shakuhachi, which is the traditional bamboo flute of Japan. I’ve done this for about 50 years now. And I perform under a performing name, Christopher Yohmei.

And in what capacity have you been connected with the Center?

I have been involved with the East-West Center since around the late 1980s, doing a number of very interesting programs with them, including Asian music, of course Japanese music, fusion, and various collaborations.

My official status at the East-West Center is that of an alumnus. I’ve been here many times for programs, workshops, performances, lectures — I was put onto their mailing list as someone of value to and connected with the Center.

How did you first become involved with the Center, and the Arts Program specifically?

I first heard of the East-West Center back in 1968 or 1969, when my former sister-in-law attended a summer session there. I was in high school at the time, and the East-West Center seemed very magical to me, mostly because it was in Hawai‘i, whereas I grew up in the flat, waterless plains of Texas.

My connection with the Center dates back to the 1980s, when I was living in Japan—I lived there from 1972 to 2016. At the time I was working as a performer, and teacher and also the Artistic Director at the International House of Japan. It was through that connection where I met Bill Feltz, the former director of the Arts Program at the East-West Center. And he was the first one who arranged my performance at the Center, which, of course, involved Japanese music. Bill was a student of Japanese music (he studied koto) and had spent time in Japan, and had a huge appreciation and interest in Japanese music.

Was there any defining moment or activity in your history and affiliation with the Center that stands out as representative of the ethos of this place as you understood it?

What I liked about Bill and his approach, and also, I realized later, constituted the basic stance of the East-West Center, was that he encouraged collaboration and outreach. He also encouraged collaborative performances between people who normally wouldn’t have the chance to play together. For example, I remember in particular one program that Bill created: a concert tour of Tsugaru shamisen, which is a northern folk shamisen tradition with very powerful performance styles and expressive singing. Tsugaru shamisen is very popular in Japan and around the world now. Bill arranged for a master shamisen player and his students, along with the master’s wife who is a singer, to do a concert tour of the United States mainland and also Hawai‘i. And here I was, as a non-Japanese, thrown into the mix, and my forte was not even folk music, but I was able to learn the style quite quickly through the help of these masters who came from Aomori, from the north part of Japan. And it was an opportunity I would never have had just on my own. It was through the interest and the focus and the generosity of the East-West Center and Bill’s avid interest in Japanese music and sharing that with a lot of people that I was able to join, take part and hopefully have made a contribution to the concert tour.

Can you tell us a little more about your musical background? Where did you study? How did you get to where you are now?

My formal musical training started in a local band in Texas playing trombone. My father played trombone and I used his old instrument. I played it in the high school marching and concert band, which was fun. And then I decided, well, the trombone is really too big to easily carry around, so I’ll switch to flute. My mother had a flute, so I started playing it. During my junior year at college I went to Japan for a foreign year abroad program, thinking I should learn some sort of Japanese flute.

There are a number of traditional flutes utilized in Japanese music, like the ryūteki and shinobue, but of all these flutes, the shakuhachi appealed to me. What was meaningful to me about the shakuhachi was its relationship to the Buddhist tradition and the overall spiritual culture of Japan. And I loved the fact that the shakuhachi is so simply made–it has only five holes, but with those five holes you can produce a variety of tones and melodies. The shakuhachi is a very limited instrument, but within those limitations you have this great expanse of possibilities. And that’s what I liked about it. It’s not complicated, it’s very simple. It’s just a piece of bamboo with five holes in it. You blow into it. But that’s where the difficult part starts. How do you blow into it? How do you create a sound? How do you create nuance and tone that can reach out and really grab your audience? And that’s what I found so fascinating and interesting about the shakuhachi.

And then later on, I got into the graduate school of the University of Fine Arts in Tokyo (Geidai), and studied gagaku with people like the ryūteki master Shiba Sensei, and of course my shakuhachi teacher, Yamuguchi Goro, along with many other wonderful teachers whom I never would have never had the chance to study with if I wasn’t in Japan at that time.

And beyond studying with them, you eventually worked collaboratively with these teachers as a fellow performer on stage. Is that correct?

It turned out that the ryūteki master Shiba sensei was also interested in contemporary music, including improvisation. So for one of my recitals I asked him to join me—here I was, this young student asking his master to perform with me–not something that happens often in the world of traditional Japanese music. I had quite the chutzpah back then! But he agreed, and I got the feeling he loved the idea, as it was something he didn’t get to do very often as a court musician. We came up with this co-improvised song called “The Night of the Garuda.” Garuda is the mythical bird of Indonesia, also ubiquitous in Thailand, that has a gigantic wingspan and eats dragons. The Garuda can symbolize many things, but to me this regal, dragon-eating bird was something I wanted to express with the music of the shakuhachi and ryūteki. The timbres of these instruments have both similarities and differences, but they seem to fit together well. As Shiba sensei is now passed, I feel it was a huge honor to have been able to work with him.

To hear “Night of the Garuda,” featuring Professor Christopher Yohmei Blasdel and Shiba sensei, please see the video below.

You can also hear more of Professor Christopher Blasdel's story and performances at his website https://www.yohmei.com/.