Error message

By Jonathan Pryke

HONOLULU (March 2, 2020)—In an atmosphere of heightened geostrategic competition, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has raised questions about the risk of debt problems in less-developed countries. Such risks are especially worrying for the small and fragile economies of the Pacific.

China is not the only donor in the region, nor the most significant. In any given year, more than 60 donors invest more than US$2 billion in aid in the Pacific, equal to around 7 percent of the region’s total gross domestic product (GDP). The vast majority of aid comes in the form of grants. These flows of aid are complex and opaque, however, and the lack of transparency hampers efforts of donors to coordinate and of recipient governments to align aid with their own priorities.

In response to concerns about this level of borrowing, the Lowy Institute created the Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map, a database with information on 20,000 projects supported by 62 donors, ranging from 2011 to today.

Drawing on this unique database and complemented by International Monetary Fund (IMF) reporting on the region, the Lowy Institute released a report in October 2019 assessing the narrative that China is engaged in “debt-trap diplomacy” in the Pacific. Although the report does not find evidence of debt-trap diplomacy at present, the sheer scale of China’s lending in a short time and its lack of strong institutional mechanisms to protect the sustainability of borrowing countries pose clear risks.

Debt sustainability risk in the Pacific

The Pacific is, by some margin, the most aid-dependent region in the world. Difficult economic geography drives an enormous need for development financing, creating a predictable pressure towards potentially unsustainable fiscal policies and debt accumulation. Pacific countries have struggled to sustain a modest pace of sustained economic growth, and many investments―even in economic infrastructure that is usually considered growth-enhancing, such as roads, ports, and power generation—struggle to generate an adequate return to justify the cost.

Chinese aid in the Pacific has predominantly supported infrastructure development. Chinese assistance is perceived to be faster, more responsive to the needs of local political elites, and with fewer conditions attached than other assistance. As one senior Pacific bureaucrat put it: “We like China because they bring red flags, not red tape.”

Six Pacific governments are currently debtors to China — Cook Islands, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Tonga, and Vanuatu — although only Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu have taken on new Chinese loans since 2016. Three small countries—Tonga, Samoa, and Vanuatu— are particularly heavily indebted.

While the IMF does not currently consider any Pacific country to be in debt distress, the risks have become notably worse over time. A primary driver behind rising debt risk is the impact of large economic shocks, especially natural disasters. Recent tropical cyclones have caused estimated damage worth more than 60 percent of GDP in Vanuatu and almost 40 per cent and 30 per cent of GDP in Tonga and Samoa, respectively. Economic mismanagement has also been important, particularly in Papua New Guinea where large budget deficits have triggered a sharp increase in public debt.

China’s role as a lender in the Pacific: Four key points

Volume of lending. While China is a major lender in the Pacific, it is not a dominant creditor. From 2011 to 2017, China was responsible for 37 per cent of all official loans disbursed in the region. Traditional creditors, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank, the IMF, Japan, and Canada, provided more than 60 per cent of all official lending. Overall, official financing flows to the Pacific have been declining in importance, driven by a sharp reduction in grant financing— notably from Australia.

Quality of projects. The Pacific is littered with failed infrastructure projects, funded by a variety of donors. A 2014 analysis, based on case studies in Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga, and Vanuatu, presented a mixed report card on the quality of Chinese projects, with some performing much better than others. The key determinants of effectiveness were the approach to negotiations taken by Pacific Island governments plus overall project oversight.

Lending terms. According to Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map data, 97 percent of China’s official loans in the Pacific have been in the form of concessional loans from its EXIM Bank. Standard EXIM concessional loans are denominated in renminbi, with an interest rate of 2 percent, a grace period of 5–7 years, and a maturity of 15–20 years. By international standards, these lending terms are quite favorable. Nonetheless, exposure to natural disasters and other vulnerabilities lower the ability of Pacific economies to carry large amounts of debt, even at favorable terms.

Lending to countries already at risk. Overall, China has not directed its lending towards countries that are already at a high risk of debt distress. Ten percent of Chinese bilateral loans have gone to countries at high risk, compared to 70 percent of bilateral loans from Taiwan, for example. Nevertheless, the sheer volume of Chinese loans, combined with the lack of strong institutional mechanisms to prevent potentially unsustainable lending, is cause for future concern.

Looking ahead

A close look at the evidence suggests that China has not been engaged in “debt-trap diplomacy” in the Pacific, at least not so far. Nonetheless, if future Chinese lending continues on a business-as-usual basis, serious problems of debt sustainability will arise, and concerns about quality and corruption are valid.

There have been recent signs that both China and Pacific Island governments recognize the need for reform. China needs to adopt formal lending rules similar to those of the multilateral development banks, providing more favorable terms to countries at greater risk of debt distress. Alternative approaches might include replacing or partially replacing EXIM loans with the interest-free loans and grants that the Chinese Ministry of Commerce already provides.

Introducing formal lending rules would offer certain advantages for China. Implementation would be relatively straightforward and would require only modest additional coordination efforts. It would also encourage greater cooperation and coordination between China, the IMF, and other official creditors, helping to reduce some of the geopolitical tensions surrounding the BRI.

Adopting formal lending rules would also help borrowing countries manage their debt more sustainably. Today, China’s state firms often engage directly with political elites when seeking agreement for new projects. In weaker-governance environments, this can mean bypassing the local finance officials normally responsible for advising on such matters. While final decisions will always rest at the political level, such practices undermine the ability of Pacific nations to manage their debt effectively. Clear rules anchoring Chinese lending to a formal assessment of debt sustainability could help address these issues by mandating early engagement with the finance officials of recipient countries on any new lending plans.

###

This East-West Wire is based on Ocean of debt? Belt and Road and debt diplomacy in the Pacific (October 2019), by Roland Rajah, Alexandre Dayant, and Jonathan Pryke. Sydney: Lowy Institute.

Download a pdf version of this Wire article.

Jonathan Pryke is Director of the Pacific Island Program at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, Australia. He can be reached at [email protected].

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. All or any part of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive Wire articles via email, subscribe here. For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see EastWestCenter.org/Journalists.

The full list of East-West Wires produced by the Research Program is available on the East-West Center website at EastWestCenter.org/Research-Wire. For more on the East-West Center Research Program, see EastWestCenter.org/Research.

The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.

Series editors:

Derek Ferrar

[email protected]

Sidney B. Westley

[email protected]

The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the East-West Center or of any other organization.

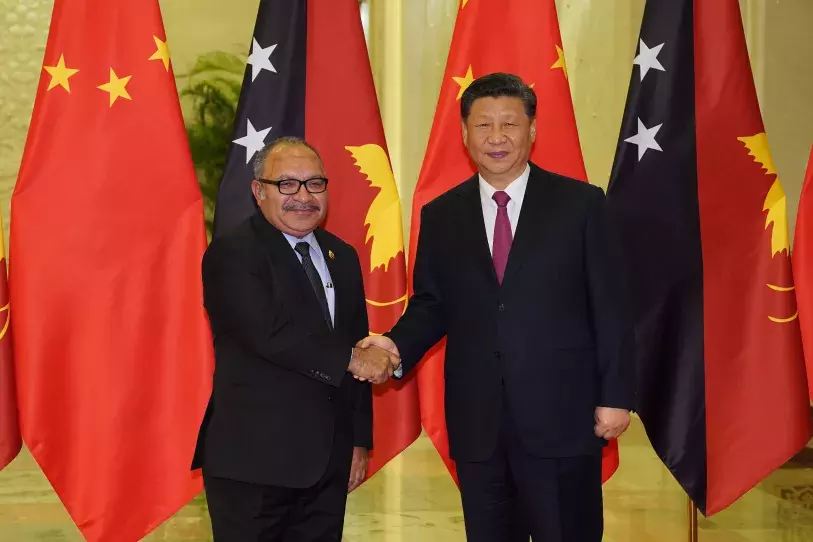

Photo: Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O'Neill (left) shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping before the bilateral meeting of the Second Belt and Road Forum on April 25, 2019, in Beijing. Credit: Andrea Verdelli/Getty Images.

By Jonathan Pryke

HONOLULU (March 2, 2020)—In an atmosphere of heightened geostrategic competition, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has raised questions about the risk of debt problems in less-developed countries. Such risks are especially worrying for the small and fragile economies of the Pacific.

China is not the only donor in the region, nor the most significant. In any given year, more than 60 donors invest more than US$2 billion in aid in the Pacific, equal to around 7 percent of the region’s total gross domestic product (GDP). The vast majority of aid comes in the form of grants. These flows of aid are complex and opaque, however, and the lack of transparency hampers efforts of donors to coordinate and of recipient governments to align aid with their own priorities.

In response to concerns about this level of borrowing, the Lowy Institute created the Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map, a database with information on 20,000 projects supported by 62 donors, ranging from 2011 to today.

Drawing on this unique database and complemented by International Monetary Fund (IMF) reporting on the region, the Lowy Institute released a report in October 2019 assessing the narrative that China is engaged in “debt-trap diplomacy” in the Pacific. Although the report does not find evidence of debt-trap diplomacy at present, the sheer scale of China’s lending in a short time and its lack of strong institutional mechanisms to protect the sustainability of borrowing countries pose clear risks.

Debt sustainability risk in the Pacific

The Pacific is, by some margin, the most aid-dependent region in the world. Difficult economic geography drives an enormous need for development financing, creating a predictable pressure towards potentially unsustainable fiscal policies and debt accumulation. Pacific countries have struggled to sustain a modest pace of sustained economic growth, and many investments―even in economic infrastructure that is usually considered growth-enhancing, such as roads, ports, and power generation—struggle to generate an adequate return to justify the cost.

Chinese aid in the Pacific has predominantly supported infrastructure development. Chinese assistance is perceived to be faster, more responsive to the needs of local political elites, and with fewer conditions attached than other assistance. As one senior Pacific bureaucrat put it: “We like China because they bring red flags, not red tape.”

Six Pacific governments are currently debtors to China — Cook Islands, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Tonga, and Vanuatu — although only Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu have taken on new Chinese loans since 2016. Three small countries—Tonga, Samoa, and Vanuatu— are particularly heavily indebted.

While the IMF does not currently consider any Pacific country to be in debt distress, the risks have become notably worse over time. A primary driver behind rising debt risk is the impact of large economic shocks, especially natural disasters. Recent tropical cyclones have caused estimated damage worth more than 60 percent of GDP in Vanuatu and almost 40 per cent and 30 per cent of GDP in Tonga and Samoa, respectively. Economic mismanagement has also been important, particularly in Papua New Guinea where large budget deficits have triggered a sharp increase in public debt.

China’s role as a lender in the Pacific: Four key points

Volume of lending. While China is a major lender in the Pacific, it is not a dominant creditor. From 2011 to 2017, China was responsible for 37 per cent of all official loans disbursed in the region. Traditional creditors, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank, the IMF, Japan, and Canada, provided more than 60 per cent of all official lending. Overall, official financing flows to the Pacific have been declining in importance, driven by a sharp reduction in grant financing— notably from Australia.

Quality of projects. The Pacific is littered with failed infrastructure projects, funded by a variety of donors. A 2014 analysis, based on case studies in Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga, and Vanuatu, presented a mixed report card on the quality of Chinese projects, with some performing much better than others. The key determinants of effectiveness were the approach to negotiations taken by Pacific Island governments plus overall project oversight.

Lending terms. According to Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map data, 97 percent of China’s official loans in the Pacific have been in the form of concessional loans from its EXIM Bank. Standard EXIM concessional loans are denominated in renminbi, with an interest rate of 2 percent, a grace period of 5–7 years, and a maturity of 15–20 years. By international standards, these lending terms are quite favorable. Nonetheless, exposure to natural disasters and other vulnerabilities lower the ability of Pacific economies to carry large amounts of debt, even at favorable terms.

Lending to countries already at risk. Overall, China has not directed its lending towards countries that are already at a high risk of debt distress. Ten percent of Chinese bilateral loans have gone to countries at high risk, compared to 70 percent of bilateral loans from Taiwan, for example. Nevertheless, the sheer volume of Chinese loans, combined with the lack of strong institutional mechanisms to prevent potentially unsustainable lending, is cause for future concern.

Looking ahead

A close look at the evidence suggests that China has not been engaged in “debt-trap diplomacy” in the Pacific, at least not so far. Nonetheless, if future Chinese lending continues on a business-as-usual basis, serious problems of debt sustainability will arise, and concerns about quality and corruption are valid.

There have been recent signs that both China and Pacific Island governments recognize the need for reform. China needs to adopt formal lending rules similar to those of the multilateral development banks, providing more favorable terms to countries at greater risk of debt distress. Alternative approaches might include replacing or partially replacing EXIM loans with the interest-free loans and grants that the Chinese Ministry of Commerce already provides.

Introducing formal lending rules would offer certain advantages for China. Implementation would be relatively straightforward and would require only modest additional coordination efforts. It would also encourage greater cooperation and coordination between China, the IMF, and other official creditors, helping to reduce some of the geopolitical tensions surrounding the BRI.

Adopting formal lending rules would also help borrowing countries manage their debt more sustainably. Today, China’s state firms often engage directly with political elites when seeking agreement for new projects. In weaker-governance environments, this can mean bypassing the local finance officials normally responsible for advising on such matters. While final decisions will always rest at the political level, such practices undermine the ability of Pacific nations to manage their debt effectively. Clear rules anchoring Chinese lending to a formal assessment of debt sustainability could help address these issues by mandating early engagement with the finance officials of recipient countries on any new lending plans.

###

This East-West Wire is based on Ocean of debt? Belt and Road and debt diplomacy in the Pacific (October 2019), by Roland Rajah, Alexandre Dayant, and Jonathan Pryke. Sydney: Lowy Institute.

Download a pdf version of this Wire article.

Jonathan Pryke is Director of the Pacific Island Program at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, Australia. He can be reached at [email protected].

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. All or any part of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive Wire articles via email, subscribe here. For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see EastWestCenter.org/Journalists.

The full list of East-West Wires produced by the Research Program is available on the East-West Center website at EastWestCenter.org/Research-Wire. For more on the East-West Center Research Program, see EastWestCenter.org/Research.

The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.

Series editors:

Derek Ferrar

[email protected]

Sidney B. Westley

[email protected]

The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the East-West Center or of any other organization.

Photo: Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O'Neill (left) shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping before the bilateral meeting of the Second Belt and Road Forum on April 25, 2019, in Beijing. Credit: Andrea Verdelli/Getty Images.

East-West Wire

News, Commentary, and Analysis

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. Any part or all of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive East-West Center Wire media releases via email, subscribe here.

For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see www.eastwestcenter.org/journalists.