Error message

By Choong Yong Ahn

HONOLULU (Oct. 10, 2018)—The rapid growth of many East and Southeast Asian economies has been fueled primarily by exports to the United States and other economies outside the region. Trade within the region has been secondary. Given the importance of bilateral trade agreements with countries in North America and Europe, multilateral agreements within the region were not a top priority.

That attitude changed after the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Concerned about their vulnerability to global financial shocks, East and Southeast Asian leaders met in Chiang Mai, Thailand, in 2000 to institutionalize a self-help mechanism based on bilateral currency swaps. After the 2008 global financial crisis, leaders “multilateralized” the Chiang Mai Initiative by adding a reserve pooling arrangement to increase the region’s bailout capacity when critically needed. Apart from setting up a regional self-help mechanism for times of financial crisis, the Chiang Mai Initiative ushered in a broader concept of intra-regional cooperation in Asia.

Changing systems of production have also fostered economic integration “from the bottom up.” Manufacturing in Asia has become increasingly fragmented as a result of growing regional and global value chains, with components and parts crossing numerous international borders. For example, Fuji Xerox, a Japanese firm, conducts product design and research and development in Japan, produces input devices in South Korea and output devices in China, assembles products at three locations, and stores final goods in Singapore for distribution around the region.

Starting in the early 2000s, East and Southeast Asian governments began placing more emphasis on regional initiatives to stimulate the free movement of goods, services, finance, and investments. The goal was to achieve more robust economic growth. By the end of 2014, 42 bilateral and sub-regional free trade agreements had been negotiated within East and Southeast Asia.

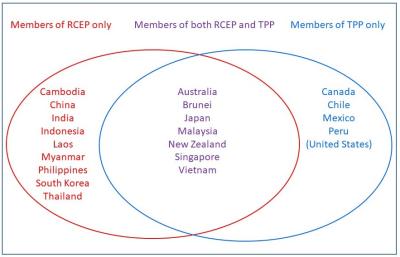

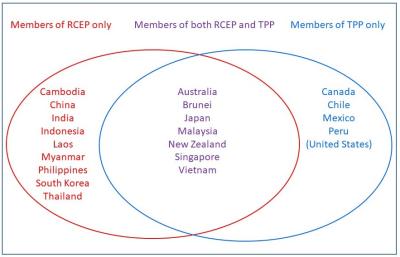

These moves toward economic integration led to two wider free-trade initiatives. The first was the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). At the end of negotiations in 2015, the TPP included 12 nations around the Pacific—Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. Then in early 2017 President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the TPP. Under Japanese leadership, the 11 remaining members are working to salvage the TPP and to add new members, but without the two largest Asia Pacific economies—the United States and China—the scope for any potential agreement is limited.

In 2012, leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) proposed a second broad free-trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This agreement brings together the 10 member states of ASEAN―Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam―plus Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. Although the Chinese did not initiate the RCEP, they have been enthusiastic supporters, partly in response to aggressive leadership by the United States, which framed the TPP in part as a check on growing Chinese influence in the region.

The terms and conditions of the TPP are quite comprehensive, going further to promote the free flow of goods and services than any other regional trade agreement. They include measures to lower tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade, support intellectual property rights, improve workers’ rights, and protect the environment. They also include measures to limit government support of state-owned enterprises that compete with private companies. These last provisions are hardly acceptable to China, where two-thirds of exports originate from state-owned enterprises.

The RCEP offers a much looser and lower level of trade and investment liberalization. To amalgamate the two trade agreements in the future in pursuit of a larger East and Southeast Asian economic community, the terms of the RCEP would need to be strengthened, particularly as related to liberalization and facilitation of trade and investment as well as rules on labor, state-owned enterprises, and the environment. After the US exit from the TPP, however, progress on both trade deals appears to have slowed down.

In December 2015, the 10 ASEAN members launched the ASEAN Economic Community, moving Southeast Asia one step closer to European-style economic integration. Within ASEAN, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam are pursuing active liberalization policies to encourage foreign direct investment, while production chains between ASEAN nations and China, Japan, and South Korea are gaining momentum.

Despite these promising moves from ASEAN members, any long-term outlook for East and Southeast Asian economic integration will be greatly affected by the bilateral relationship between the United States and China. Will these two great powers collide or collaborate or will they take a mixed stance in pursuit of their national interests? And will the two proposed mega free-trade agreements—the TPP and the RCEP—compete for influence in the region or interact to become mutually reinforcing parallel tracks for regional integration?

Given the complexity and time-consuming process of negotiating a formal, top-down system of economic integration, East and Southeast Asian countries need to prepare by tackling the easy issues first. These include measures to facilitate trade, such as e-customs services, rule of origin verification, intellectual property rights protection, and integrated management of supply chains. The promotion of intra-regional tourism and student exchanges could also create jobs and enhance cultural understanding.

Another valuable addition would be an intra-regional coordination mechanism to deal with the effects of natural disasters. East and Southeast Asian economies could also fruitfully collaborate more effectively on non-traditional security issues, including nuclear safety, energy security, green growth strategies, and cyber terrorism.

Nearly all the negotiating members of the TPP and the RCEP are members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) entity, and seven APEC members (Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam) belong to both the TPP and RCEP. Although the development of APEC has been slow and non-binding, the United States, China, Japan, and the remaining APEC member states remain engaged in the pursuit of APEC’s ideal for an Asia-Pacific community—specifically a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). It is critically important today to sustain this vision and to see it realized.

Choong Yong Ahn, is Professor Emeritus in the College of Business and Economics at Chung-Ang University, South Korea, and former Chairman of the Korea Commission for Corporate Partnership. He also served as President of the Korea Institute of International Economic Policy and Chair of the APEC Economic Committee.

This issue of the East-West Wire is based on “Toward an East Asian economic community: Prospects and challenges,” a lecture presented by Professor Ahn in August 2018 at the East-West Center’s International Alumni Conference in Seoul; and on Professor Ahn’s chapter by the same title in Peter Hayes and Chung-In Moon, eds., The future of East Asia (Asia today), Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

This East-West Wire is available in pdf format.

##

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. All or any part of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive Wire articles via email, subscribe here. For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see www.eastwestcenter.org/journalists.

The full list of East-West Wires produced by the Research Program is available on the East-West Center website. For more on the East-West Center Research Program, see www.eastwestcenter.org/research.

The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.

Series editors:

Derek Ferrar

[email protected]

Sidney B. Westley

[email protected]

By Choong Yong Ahn

HONOLULU (Oct. 10, 2018)—The rapid growth of many East and Southeast Asian economies has been fueled primarily by exports to the United States and other economies outside the region. Trade within the region has been secondary. Given the importance of bilateral trade agreements with countries in North America and Europe, multilateral agreements within the region were not a top priority.

That attitude changed after the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Concerned about their vulnerability to global financial shocks, East and Southeast Asian leaders met in Chiang Mai, Thailand, in 2000 to institutionalize a self-help mechanism based on bilateral currency swaps. After the 2008 global financial crisis, leaders “multilateralized” the Chiang Mai Initiative by adding a reserve pooling arrangement to increase the region’s bailout capacity when critically needed. Apart from setting up a regional self-help mechanism for times of financial crisis, the Chiang Mai Initiative ushered in a broader concept of intra-regional cooperation in Asia.

Changing systems of production have also fostered economic integration “from the bottom up.” Manufacturing in Asia has become increasingly fragmented as a result of growing regional and global value chains, with components and parts crossing numerous international borders. For example, Fuji Xerox, a Japanese firm, conducts product design and research and development in Japan, produces input devices in South Korea and output devices in China, assembles products at three locations, and stores final goods in Singapore for distribution around the region.

Starting in the early 2000s, East and Southeast Asian governments began placing more emphasis on regional initiatives to stimulate the free movement of goods, services, finance, and investments. The goal was to achieve more robust economic growth. By the end of 2014, 42 bilateral and sub-regional free trade agreements had been negotiated within East and Southeast Asia.

These moves toward economic integration led to two wider free-trade initiatives. The first was the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). At the end of negotiations in 2015, the TPP included 12 nations around the Pacific—Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. Then in early 2017 President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the TPP. Under Japanese leadership, the 11 remaining members are working to salvage the TPP and to add new members, but without the two largest Asia Pacific economies—the United States and China—the scope for any potential agreement is limited.

In 2012, leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) proposed a second broad free-trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This agreement brings together the 10 member states of ASEAN―Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam―plus Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. Although the Chinese did not initiate the RCEP, they have been enthusiastic supporters, partly in response to aggressive leadership by the United States, which framed the TPP in part as a check on growing Chinese influence in the region.

The terms and conditions of the TPP are quite comprehensive, going further to promote the free flow of goods and services than any other regional trade agreement. They include measures to lower tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade, support intellectual property rights, improve workers’ rights, and protect the environment. They also include measures to limit government support of state-owned enterprises that compete with private companies. These last provisions are hardly acceptable to China, where two-thirds of exports originate from state-owned enterprises.

The RCEP offers a much looser and lower level of trade and investment liberalization. To amalgamate the two trade agreements in the future in pursuit of a larger East and Southeast Asian economic community, the terms of the RCEP would need to be strengthened, particularly as related to liberalization and facilitation of trade and investment as well as rules on labor, state-owned enterprises, and the environment. After the US exit from the TPP, however, progress on both trade deals appears to have slowed down.

In December 2015, the 10 ASEAN members launched the ASEAN Economic Community, moving Southeast Asia one step closer to European-style economic integration. Within ASEAN, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam are pursuing active liberalization policies to encourage foreign direct investment, while production chains between ASEAN nations and China, Japan, and South Korea are gaining momentum.

Despite these promising moves from ASEAN members, any long-term outlook for East and Southeast Asian economic integration will be greatly affected by the bilateral relationship between the United States and China. Will these two great powers collide or collaborate or will they take a mixed stance in pursuit of their national interests? And will the two proposed mega free-trade agreements—the TPP and the RCEP—compete for influence in the region or interact to become mutually reinforcing parallel tracks for regional integration?

Given the complexity and time-consuming process of negotiating a formal, top-down system of economic integration, East and Southeast Asian countries need to prepare by tackling the easy issues first. These include measures to facilitate trade, such as e-customs services, rule of origin verification, intellectual property rights protection, and integrated management of supply chains. The promotion of intra-regional tourism and student exchanges could also create jobs and enhance cultural understanding.

Another valuable addition would be an intra-regional coordination mechanism to deal with the effects of natural disasters. East and Southeast Asian economies could also fruitfully collaborate more effectively on non-traditional security issues, including nuclear safety, energy security, green growth strategies, and cyber terrorism.

Nearly all the negotiating members of the TPP and the RCEP are members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) entity, and seven APEC members (Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam) belong to both the TPP and RCEP. Although the development of APEC has been slow and non-binding, the United States, China, Japan, and the remaining APEC member states remain engaged in the pursuit of APEC’s ideal for an Asia-Pacific community—specifically a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). It is critically important today to sustain this vision and to see it realized.

Choong Yong Ahn, is Professor Emeritus in the College of Business and Economics at Chung-Ang University, South Korea, and former Chairman of the Korea Commission for Corporate Partnership. He also served as President of the Korea Institute of International Economic Policy and Chair of the APEC Economic Committee.

This issue of the East-West Wire is based on “Toward an East Asian economic community: Prospects and challenges,” a lecture presented by Professor Ahn in August 2018 at the East-West Center’s International Alumni Conference in Seoul; and on Professor Ahn’s chapter by the same title in Peter Hayes and Chung-In Moon, eds., The future of East Asia (Asia today), Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

This East-West Wire is available in pdf format.

##

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. All or any part of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive Wire articles via email, subscribe here. For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see www.eastwestcenter.org/journalists.

The full list of East-West Wires produced by the Research Program is available on the East-West Center website. For more on the East-West Center Research Program, see www.eastwestcenter.org/research.

The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.

Series editors:

Derek Ferrar

[email protected]

Sidney B. Westley

[email protected]

East-West Wire

News, Commentary, and Analysis

The East-West Wire is a news, commentary, and analysis service provided by the East-West Center in Honolulu. Any part or all of the Wire content may be used by media with attribution to the East-West Center or the person quoted. To receive East-West Center Wire media releases via email, subscribe here.

For links to all East-West Center media programs, fellowships and services, see www.eastwestcenter.org/journalists.